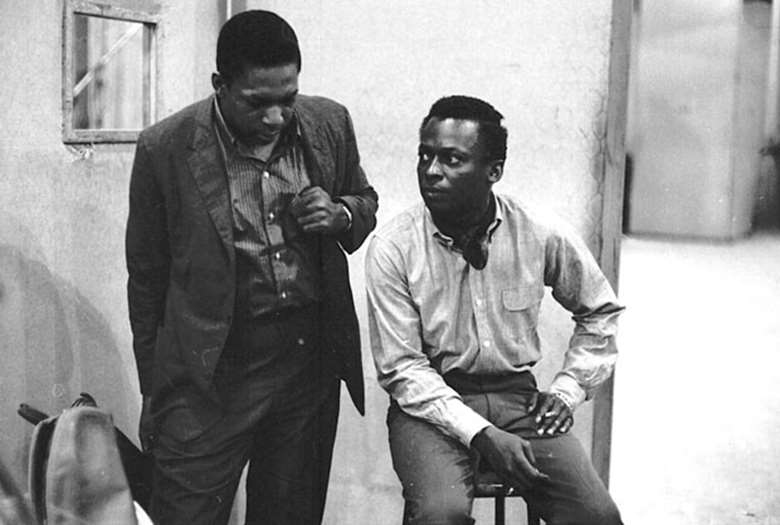

Miles Davis and John Coltrane: Yin and Yang

Ashley Kahn

Monday, January 2, 2023

How did John Coltrane and Miles Davis get on? The odd couple, with contrasting personalities on and off the bandstand. But together the music they produced was peerless

Ice and fire they were: a two-horned paradox. Offstage, one was quiet, pensive, self-critical to a fault, practising obsessively. The other was cocksure, demanding; running with friends rather than running scales. But on the bandstand and on record, they reversed roles. John Coltrane, with saxophone in hand, became the unbridled one: long-winded, garrulous. When Miles Davis raised his trumpet, he played the sensitive introvert, blowing brief, hushed tones, exuding vulnerability.

Their names now command reverence, and rarely induce less than eulogy. The music they created together during an almost five-year union still resonates, entrances, influences and sells, sells, sells. Miles’ 1959 classic album Miles Davis – Kind of Blue marking the apex of their collaborative years – stands as the most popular jazz album of all time, loved by a vast, non-partisan spectrum of music consumers. Their absence has only succeeded – like Sinatra, like Presley, like a rarefied few – in intensifying their recognition and elevating their legend.

September, 1955: the trumpeter was desperate. He was preparing for his first national tour arranged by a high-powered booking agent. Columbia Records – the most prestigious and financially generous record company around – was looking over his shoulder, checking on him. 'If you can get and keep a group together, I will record that group,’ George Avakian, Columbia’s top jazz man, had promised. To Miles, an alumnus of Charlie Parker’s groundbreaking bebop quintet, ’group’ meant a rhythm trio plus two horn players, but he still had only one: himself.

For the up-and-coming trumpeter, the preceding summer had been filled with promise. He was clean and strong, six months after kicking a narcotics habit he described as a ‘four year horror show’. His popular comeback had been hailed when, unannounced, he had walked on to the Newport Jazz Festival stage in July and wowed a coterie of America's top critics with a low, laconic solo on 'Round About Midnight'. And Davis had the foundation of his dream quintet firmly in place: Texas-born Red Garland on piano, young Paul Chambers from Detroit on bass and the explosive (and his former junk-partner) Philly Joe Jones on drums.

For the up-and-coming trumpeter, the preceding summer had been filled with promise. He was clean and strong, six months after kicking a narcotics habit he described as a ‘four year horror show’. His popular comeback had been hailed when, unannounced, he had walked on to the Newport Jazz Festival stage in July and wowed a coterie of America's top critics with a low, laconic solo on 'Round About Midnight'. And Davis had the foundation of his dream quintet firmly in place: Texas-born Red Garland on piano, young Paul Chambers from Detroit on bass and the explosive (and his former junk-partner) Philly Joe Jones on drums.

But Sonny Rollins had disappeared. Miles’ chosen tenorman from Harlem – blessed with a free-flowing horn-style and dexterous sense of rhythm – had long been threatening to leave town. Rollins, it later turned out, checked himself into a barred-window facility in Kentucky to kick his own drug addiction. Davis – with time running out – shifted his recruiting drive into top gear.

A number of possibilities topped the list: Julian 'Cannonball' Adderley, the new alto sensation from Tampa was one. Sun Ra’s accomplished tenorman John Gilmore was another. But the former had to return to Florida to complete a teaching contract, and the latter simply 'didn’t fit in', as Miles remembered.

Meanwhile in Philadelphia, John Coltrane, a tenor player not on Davis' short list but with a respectable – albeit local – reputation, was playing in organist Jimmy Smith’s combo. Philly Joe made Miles aware of his availability.

Coltrane was not unknown to Davis. As early as 1946, he had been impressed by an acetate of an impromptu bebop session recorded during the saxophonist's tour of duty in the navy. Coltrane’s subsequent tenure in Dizzy Gillespie’s big band brought the two in contact. In his autobiography, Davis recalled with glee a memorable match-up he orchestrated in 1952.

'I used Sonny Rollins and Coltrane on tenors at a gig I had at the Audobon Ballroom... Sonny was awesome that night, scared the shit out of Trane.’

When Coltrane arrived in New York to audition with the group, Miles was not expecting much. But the saxophonist surprised him. ‘I could hear how Trane had gotten a whole lot better than he was on that night Sonny set his ears and ass on fire,’ Davis recalled.

What Miles heard was a sound that, though still developing, was singular and unheard. Almost all tenor players at that point blew under the spell of one of two, massively influential pioneers: the brash, highly rhythmic Coleman Hawkins or the breathy, understated Lester Young. Even the much-heralded, innovative playing of Dexter Gordon – an early stylistic model for Coltrane – vacillated between those two stylistic poles.

But Coltrane was searching for something original, and that search was part of his sound. He repeated phrases as if he was wringing every possibility out of note combinations. He was determined never to play predictable melodic lines; instead, unusual flourishes and rhythmic fanfares cut through the structure of the tune. Many writers would puzzle over – some actively denounce – this new, 'exposed' style. They were familiar with polish, not process. Was he practising or performing? Was that harsh rasp intentional, or just a loose mouthpiece? Why were his solos so long?

Miles could not have cared less about the critics (though he later responded when Coltrane admitted difficulty ending his extended improvisations: 'Try taking the saxophone out of your mouth’). As Davis proved time and again through his career, he had an uncanny ability to detect greatness in the bud. 'People have creative periods, periods where they (snaps fingers three times), like that, you know?’ Miles humbly informed Ben Sidran in 1986. 'I recognise it in other people.'

Miles recognised it at that first rehearsal, but kept his excitement hidden. Coltrane, unaware of his reaction and used to a sideman role, requested direction. Davis responded curtly and discourteously, unnerved that a self-professed jazz player required spoken instruction. ‘My silence and evil looks probably turned him off,’ he admitted later.

Meeting an unexpectedly cold draft, Coltrane packed his horn and returned home disgruntled, ready to rejoin Jimmy Smith. But there was method behind Miles’ muteness, as the pianist Bill Evans whose nine-month term with Miles would overlap Coltrane’s shift – understood.

It was a lesson in nuance Coltrane later exploited with great consequence in his own groups. But at that point, whether or not the saxophonist was hip or original enough was suddenly less important than Miles' immediate need. Trane was the only one who knew all the tunes,’ Miles later wrote. ‘I couldn’t risk have nobody who didn’t know the tunes.' He instructed Philly Joe to call back Coltrane.

At first glance, it reads like a recipe for discontent: a sullen, guarded, complex personality – extremely so in Davis’ case hiring another who was just as intense, but in a sincere and humble way. And beyond differences in temperament, their backgrounds predicted discord.

Coltrane was the scion of a middle-class, religious family – both his grandfathers were ministers – and came from a small country hamlet in central North Carolina. A series of deaths left him the sole male figure in his family at the age of 13, causing him hardship both financial and emotional. Turning inward, he relied on music for solace and spiritual strength; outwardly he remained quiet and serious, with an air of innocence about him. His professional career evolved slowly; 10 years of journeyman gigs in a variety of bands – blues, R&B and jazz – preceded his joining Davis.

Miles Dewey Davis III was born to and raised in privilege. Miles II, a college-educated dentist and landowner, bankrolled his son's musical education and errant, drug-filled years. Headstrong and fortunate, the young trumpeter made it into Charlie Parker’s groundbreaking bebop quintet by the ripe age of 19, benefiting and making the most of the association at a rapid rate. By 1947, he was recording under his own name and topping jazz critic polls.

But to the two intrepid jazz men, it was the music that mattered above all else, set them on parallel paths and ultimately brought them together. Both Coltrane and Davis were charter members of a determined jazz brotherhood who saw themselves as serious artists rather than entertainers, and their music as deserving the same respect and regard as other high-brow forms of culture. Both matured from the big band era of the 1940s, fell under the spell of bebop, and spearheaded jazz through its small-group heyday of the 50s and well into the 60s. Both were junkies who traded heroin for harmony, going cold turkey for the sake of their music.

Had their respective natures not yin-yanged so effectively, perhaps the Coltrane/Davis union never would have survived as long as it did. Given the nature of their characters and careers, it’s hard to imagine the two together in any other fashion than a complementary, master/pupil relationship. Predictably, as their music developed, and as Coltrane's confidence grew, so the bonds of that union were tested and retested. Like so many fertile musical unions, they loved and respected, suffered and fought with each other.

Coltrane solemnly and ceaselessly studied music exercise books; Miles would write out chord sequences on matchbooks, ruminating for hours on one musical puzzle

Most importantly, both were musical explorers, driven by a gnawing hunger to learn, to change and to hone their craft. Coltrane solemnly and ceaselessly studied music exercise books; Miles would write out chord sequences on matchbooks, ruminating for hours on one musical puzzle. As they eventually grew comfortable in the close proximity of the road, Davis opened up and shared his passion. ‘We used to talk a lot about music at rehearsals and on the way to gigs I'd say, "Trane, here are some chords but don’t play them like they are all the time, you know? Start in the middle sometimes and don’t forget you can play them up in thirds. So that means you got 18, 19 different things to play in two bars." He would sit there, eyes wide open, soaking up everything.’

Free from the more limited musical challenges of big bands, earning and learning in the greenhouse that was Davis' group, Coltrane blossomed. His self-education was pushed into high gear nightly, propelled by an ace rhythm section. When not onstage, Coltrane could be heard constantly rehearsing alone: backstage, in the club’s kitchen, in his hotel room.

'As much as I liked Trane we didn’t hang out much once we left the bandstand because we had different styles... he didn't hang out much,' Miles stated, shaking his head, and marvelling at his sideman's total focus. He was just into playing, was all the way into the music,’ Davis recalled. 'If a woman was standing right in front of him naked, he wouldn't even have seen her. That’s how much concentration he had when he played.’ To the chagrin of many writers and fans, Davis began leaving the bandstand while still in performance to better hear, and not distract from, his sideman's solos.

January, 1956: During the group's first visit to Los Angeles, tenorman Stan Getz begged to sit in. Miles consented, sat at a table and watched as his new protege blew one of the prime purveyors of the California-based, 'Cool' jazz school off the bandstand.

'It destroyed West Coast jazz overnight,’ one witness reported. 'There were a few of us who got an immediate positive reaction to Trane.’

As the sound of the entire quintet was a sizzling, ear-grabbing study in contrasts – sophisticated yet funky, swinging hard but with a laid-back, lyrical ease – so Miles soon realised that he had found not just a great sideman in Coltrane, but the perfect counterpoint to his own subdued trumpet. 'After we started playing together for a while,' he later revealed, using his favourite term of endearment, 'I knew that this guy was a bad motherfucker who was just the voice I needed on tenor to set off my voice.'

'Trane’s Blues' – an overlooked gem composed by Coltrane from the quintet’s second recording session for Prestige Records in May of 1956 – is a telling example of their side-by-side effect. Serene and poised, Miles phrases his solo like an off-hand chat, playing off the light swing of the tune, pausing, allowing space to breathe in between the notes. A slight drum roll introduces Coltrane. More assertive in tone, he answers Davis, building a rougher, more urgent reply, but still finding loose, melodic lines that lead him to longer statements.

Their contrasting approach was even more pronounced during performances, and less balanced. Often, Coltrane would take three, four, even five times as much time for his improvisations. Their own words revealed the reason: Miles listened for 'what can be cut out'; for Coltrane, ‘it took that long to get it all in.’

Solo lengths notwithstanding, the quintet coalesced and clicked, its success and popularity growing at a swift rate. Unfortunately, as it toured coast-to-coast, the group – and particularly Coltrane – carried a pernicious problem that was growing just as rapidly: the burden of drug addiction.

As Miles remembered in his autobiography, Coltrane’s habit began to get the better of him, to the point of threatening his future with the group. Davis reported his star saxophonist showing up to gigs in rumpled clothing, picking his nose distractedly and nodding out onstage, drinking heavily at the bar when he could not score. Miles initially resisted judgment, knowing only too well the suffering Coltrane was experiencing. 'I just tell them if they work for me to regulate their habit,’ Miles shrugged. 'You can't talk a man out of a habit until he really wants to stop.'

Exasperated, the diminutive trumpeter slapped his taller sideman in the head, and slugged him in the stomach

October, 1956: Miles could take it no longer. In a now legendary pique at New York’s Cafe Bohemia, Davis berated Coltrane for his slovenly appearance and tardiness. The saxophonist was too much in a stupor to respond with anything but silence. Exasperated, the diminutive trumpeter slapped his taller sideman in the head, and slugged him in the stomach. Coltrane still offered no resistance. A non-plussed Thelonious Monk witnessed the one-sided argument, stepped in and urged the saxophonist to quit and join his band.

A man with higher self-regard might have struck back or at least walked away for good, but Coltrane was an extremely humble, non-violent man. And with a young family and a growing habit to support, he desperately needed the pay. Despite the assault on body and pride, he intermittently returned to Miles over the next few months. But Davis’ blow up was only followed by further disappointment; in April, 1957, he ran out of patience and fired both Coltrane and Jones for ‘their junkie shit.’

It was a wake up call for Coltrane, hitting him harder than any well-aimed punch. Leaning on friends and family for support – and relying on a burgeoning spirituality influenced by his church-based roots and his wife Juanita’s embracing of Islam (by then calling herself Naima) – he returned home to Philadelphia, and put the needle and bottle forever behind him. Fittingly, upon his return to New York – clean and revitalised – he entered the studio and recorded his debut as a leader: First Trane.

December 1957: Miles, back from a tour of France, had a vision. After getting through most of the year without Coltrane, after a series of replacements that included Sonny Rollins, the trumpeter had eventually lured Cannonball Adderiey into the band. But Miles had not forgotten his former tenor player; ‘I had this idea in my head of expanding the group from a quintet to a sextet, with Trane and Cannonball on saxophones...'

Much had changed in Miles' group. Tired of a scene that felt littered with musical cliches and formulas left over from the heyday of bebop, Davis was pursuing a path that became known as modal jazz. His compositions began to rely on scales rather than established chord patterns, as both tempo and harmonic movement of the music downshifted. With few or no chordal patterns available on which to hang his notes, Miles forced his soloists to rely on their own innate sense of melody to improvise and express.

Meanwhile, Coltrane had enjoyed a six-month residency playing with Thelonious Monk in Manhattan's East Village, honing the scale-skipping flurries that defined his ‘sheets of sound’ style. What began as a faltering attempt to grasp Monk’s idiosyncratic approach to chord structure and rhythm, became a crash course in harmonic flexibility. Much like his ongoing dialogue with Miles, Coltrane reported: ‘I would talk to Monk about musical problems, and he would sit at the piano and show me the answers just by playing them.’

Coltrane's intrepid spirit had led him to probe the very nature of his saxophone, ostensibly a single-note instrument. He learned to adjust his mouth on the reed and – with Monk’s tutoring – use unorthodox fingering, finding a way to actually voice two or three notes at once and play chords through his horn.

When Coltrane resumed with Miles that final week of the year, the result was a creative pressure cooker wherein the tenorman's blues roots and recent rule-bending experiments dovetailed perfectly with the challenge of an expanded lineup and a new modal form of music.

From 1958-59, whenever Coltrane and Miles performed and the tapes were rolling, the full promise of their collaborative magic was finally fulfilled. What had been great jazz from Davis' 1955-7 quintet, now broke through to a category of timelessness as recorded by the trumpeter’s sextet in 1958 and 1959. Even their impromptu live recordings merit focused listening. But the two masterful studio albums from this period – Milestones and Kind of Blue – are list-topping must-haves for any jazz enthusiast, any student of 20th century music, any music lover. Anyone with ears.

It’s no coincidence that Coltrane recorded his own chord-based masterpiece – Giant Steps – only two weeks after Kind of Blue. The same maturity and self-assurance powers his work on both. But the former album is significant as his declaration of creative independence, acknowledging Coltrane’s arrival as a fully matured, triple threat: soloist, bandleader and composer. His musical vision was leading him in a direction away from Miles, and there was only room for one leader in the trumpeter’s band. The bonds of their bossman/hired hand relationship were straining.

Miles keenly sensed Coltrane drifting away, just as he felt how frustrating it would inevitably be to find a replacement of equal talent. As Davis confessed, he tried to both expedite and defer their parting.

'It was hard for [Coltrane] to bring up that he wanted to leave... but he did bring it up finally and we made a compromise: I turned him on to [my manager] Harold Lovett... to handle his financial affairs. And then Harold got him a recording contract [and] set up a publishing company for Trane... To keep Trane in the band longer, I asked Jack Whittemore, my agent, to get bookings for Trane's group whenever we weren't playing, and he did.’

March, 1960: Coltrane grumbled his way through a month-long tour of Europe, his last with Miles, his mind more on his own music. Though scheduled to appear as headliner at the Five Spot for most of the month, he had cancelled the appearance, agreeing to accompany Davis, his one blue suit and two white shirts testament to his reluctant, last-minute decision. If his irritable attitude did not make it clear that his time as a mere band member was finally up, a tape from the group's Paris performance certainly does.

Miles offered a familiar song list meant to satisfy fans both new and diehard. When Coltrane stepped to the microphone, a breathless flurry cascaded forth. As Davis left the stage, he played on and on, pushing the saxophone like a racehorse, leaping between registers, finding sounds that tested ears attuned to the more mellow solos on Kind of Blue.

For the first time, most Parisians were witnessing the raw, boundless intensity that was Coltrane’s trademark for the rest of his career; the tentative, experimental breeze Miles had felt in 1955 was becoming a full-force gale.

On the tape, each tune comes across like three different bands, depending on the soloist: Miles, Coltrane or the pianist Wynton Kelly. But during the saxophonist’s solos, one can hear the crowd growing restless: whistling and arguments erupt in the audience.

French propensity to vocally express dissatisfaction notwithstanding, Coltrane had outgrown his role with Miles and the music he was playing. The trumpeter's modal experiments launched the saxophonist out of the band in a totally different musical direction.

When the group landed back in New York in early April 1960, save for a few impromptu night club jams and one more studio session, the Coltrane-Davis coalition reached its coda.

How the two looked back on their time together can be divined in how each continued to look upon the other. Years after Coltrane evolved into a bandleader of renown and many disciples, Alice Coltrane recalls he still reverently called Davis 'The Teacher'. Miles was typically more oblique. When speaking with jazz critic Ralph J. Gleason in the late 60s, the journalist noted that Davis' music had become complex enough to demand five tenor players. Gleason recorded his response: 'He shot those eyes at me and growled, "I had five tenor players once." I knew what he meant.'

This article originally appeared in the December 2001 issue of Jazzwise. Photos by Dan Hunstein, courtesy of Sony Music

Never miss an issue of Jazzwise magazine – subscribe today