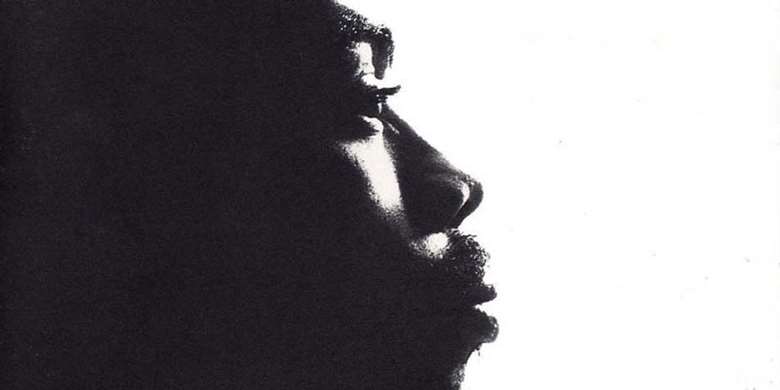

Eric Dolphy

Kevin Le Gendre

With a penchant for stark, sometimes acerbic themes set to rhythms that move abruptly from swing to pedal point, Dolphy delighted in making music with a brash, daredevil energy

Sadly, the pantheon of black music is peopled by souls who passed away far too early. As an artist who died at the age of 36 Eric Dolphy is a particularly poignant example of the phenomenon, all the more so because it is rumoured that adequate treatment for his diabetes was withheld on at least one occasion because it was assumed that a jazz musician had a substance abuse problem rather than a common medical condition.

Dolphy’s considerable achievements during his lifetime provide something of a counterweight to that tragedy. Born and raised in Los Angeles, he became a vital member of the ‘50s west coast scene, playing with respected bandleaders such as Gerald Wilson and Chico Hamilton, and more or less set the template for the multi-reed player, supplementing his alto saxophone and clarinet with flute and bass clarinet, an instrument introduced to him by Marzette Watts that Dolphy would subsequently bring to prominence.

In many ways Dolphy was one of the key bridges between the bebop and avant-garde schools insofar as he was adept at playing on chord changes and in more harmonically open situations where his rapid flow of notes sometimes gives the impression he himself can barely keep abreast of his own ideas.

Working with progressives such as saxophonist Oliver Nelson, pianist Mal Waldron and trumpeter Booker Little, Dolphy recorded a series of consistently strong albums throughout the ‘60s, such as The Five Spot Sessions [with Little] Out There, Outward Bound and Music Matador, in which his composing and playing hit notable creative peaks.

With a penchant for stark, sometimes acerbic themes set to rhythms that move abruptly from swing to pedal point, Dolphy delighted in making music with a brash, daredevil energy, which was underlined by improvisations that had a kind of whistle, siren and alarm bell character due to his use of large intervals and withering flurries of sixteenth notes.

Nowhere is this more compelling than on his masterpiece Out To Lunch, an album in which the relatively unconventional line-up – with Bobby Hutcherson’s vibraphone replacing the expected piano – superb writing and playing produced a kind of intricate, vibrant carousel of sounds that had the gravitas of the most advanced jazz and classical music. While the memorable cover of a clock with hands whizzing in all directions pointed to the mercurial, unpredictable nature of the music, Hutcherson made a telling observation on its real significance.”That clock… was Eric.”

Some of Dolphy’s most adventurous performances came in the company of several other saxophone icons, John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman [Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation], but there was also a serene, tender side to his musical character that was expressed in the sublime ballads in his songbook, none more so than ‘Warm Canto’, a reminder of Dolphy’s sensitivity as well as intellectual energy.