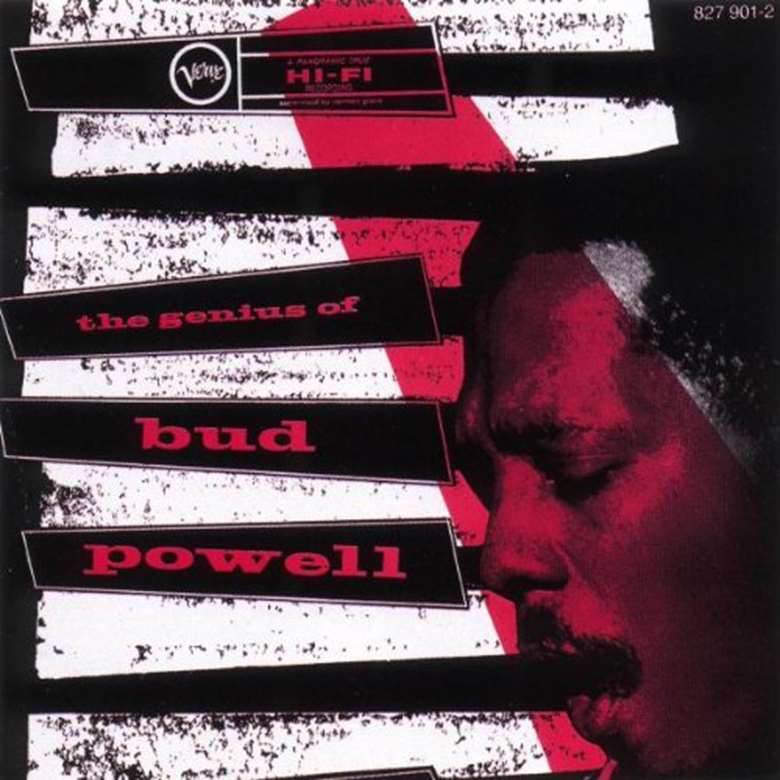

Bud Powell

Kevin Le Gendre

Bud Powell developed a style that had a sweeping grandeur when he played at the high tempos beloved of the gifted horn players – such as Gillespie and ‘Fats’ Navarro – he admired and worked with

At the 2017 London Jazz Festival there was a worthwhile debate on mental health in improvised music, with the centenary of Thelonious Monk being the relevant hook. The case of Bud Powell could just as easily been the premise, given the fact that he is also one of the brilliant exponents of bebop whose life was severely blighted by more than psychiatric problems, exacerbated as they were by a severe beating at the hands of the police, the austerity of the institutions where he was treated also had an impact.

Electro-convulsive therapy was brutal for him. So too the attitude of consultants who, quite shockingly, mistook Powell for a fantasist – “Claims to have made records,” read one particularly heartless report. It goes to show the extent of ignorance, snobbery and, most likely racism, that ran through a medical establishment for which Negro musicians, with their ‘crazy rhythms’, were not seen as valid artists.

If the doctors had bothered to check they would have seen that Powell had already made an enormous impression both in the studio, with his first trio sessions in 1947, and on stage, particularly at New York’s fabled Minton’s Playhouse, epicentre of the innovations of Diz, Bird, Monk et al, and at the lesser-known Clique Club.

Influenced by Monk’s singular harmony and the rhythmic-melodic sparkle of Art Tatum, Powell developed a style that had a sweeping grandeur when he played at the high tempos beloved of the gifted horn players – such as Gillespie and ‘Fats’ Navarro – he admired and worked with.

‘Tempus Fugue-It [Tempus Fugit]’ is a definitive Powell piece for a number of reasons. The pun in the title makes reference to the classical training he had as a child but the English translation of the Latin phrase – ‘Time flies’ – can be seen as a symbol for the invigoration of his performance, whereby rhythmic momentum and improvisatory prowess conspire to make the piece into both exhilarating steeplechase and breathless sprint.

The 1949 trio version of the piece, with Ray Brown on double bass and Max Roach on drums, is a definitive example of Powell’s astonishingly fluency, where the end of one phrase elides neatly into beginning of the next and flashing chromaticism increases the sense of the music surging forward like toppling dominos.

That flourish also came to the fore in solo piano performances, where the finer points of Powell’s technique, and in particular, his carefully staggered left hand, are outstanding. Although Powell recorded steadily in New York throughout the ‘50s he was greatly affected by the death of his brother Richie in a car accident and became increasingly dependent on drugs and alcohol.

His relocation to Paris at the end of the decade brought him a degree of solace but he sadly went into rapid decline as he was unable to shake his personal demons.

Dead at the tragically young age of 42, Powell nonetheless exerted an enormous influence in his lifetime and remains a core part of the vocabulary for all improvising pianists. Furthermore, his place in the long running relationship American jazz has had with both Paris and French cinema was cemented by the fact that his life, as documented in Francis Paudras’ book Dance Of The Infidels, formed the basis for Bertrand Tavernier’s engrossing 1986 feature film Autour De Minuit [Round Midnight].