Black British bloodlines and Humph’s favourite singer

Val Wilmer

Thursday, September 12, 2024

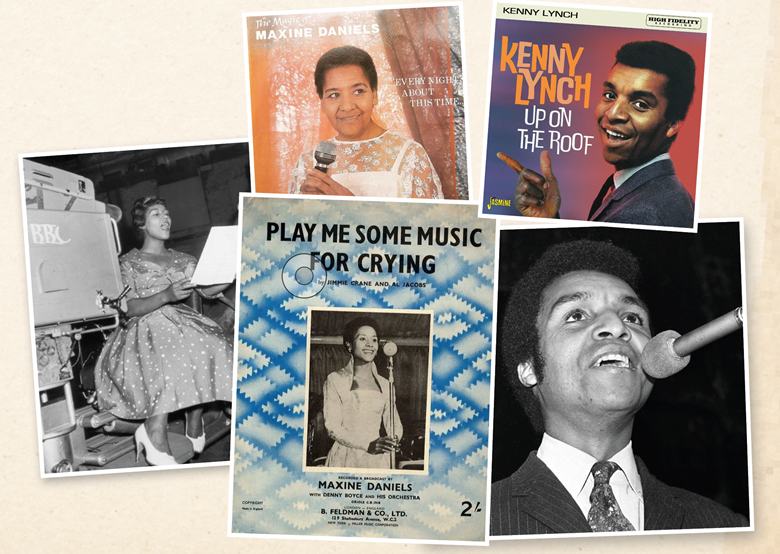

Maxine Daniels, big sister of actor and singer Kenny Lynch, was a successful and pioneering vocalist – and member of the Humphrey Lyttelton band – in the 1950s and 60s. She deserves to be better remembered today, argues Val Wilmer in this fascinating study of 20th Century East End London black life

I’m looking at a photograph of a wedding in Poplar, in London’s East End, in July 1950. Charlie Daniels and Gladys Lynch are a good-looking pair. He is a stoker from Plaistow, she is working as a packer; but she is about to make a name for herself as a singer. She is Maxine Daniels, part of the story of black British music overlooked by the recent [British Library] exhibition. The picture itself is faded, but redolent with historical links.

The 31 people gathered outside the Parish Church of All Saints are Eastenders. Nearly all are people of colour, with skin shades ranging from the darkest to near-white. Africa is quite a way in the past. The bridal pair’s fathers were Caribbean seamen who came to London around the First World War, and married local women. Nathaniel Daniels, from the tiny Union Island in the Grenadines, married Maggie (née Pye). Gladys was the daughter of Oliver Lindsay Lynch, a Barbadian employed as a stoker at Becton Gas Works; her mother was Amelia Mary Ann (née Spring). In the foreground, standing beside his father and wearing short trousers, with a hint of a ’cheeky chappy’ look, is the bride’s 12-year-old brother. His name is Kenneth, and he didn’t do badly, either.

Gladys already had a reputation when she walked down the aisle. She sang with a local band, and won second place in a singing contest. This led to a job with an established dance band, and when leader Denny Boyce suggested she find a more professional name, (“Gladys is too much like a barmaid”), she chose Maxine after the African-American singer, Maxine Sullivan, one of her favourites.

Regular broadcasts on Radio Luxembourg brought Maxine Daniels a wider audience and a recording contract with the Oriole label. She left Boyce to work as a solo artist, first in the variety theatres, then in cabaret. She worked on the continent, played American bases, and did some acting, but her true home was with the band of trumpeter Hurnphrey Lyttelton, a musician with a penchant for bringing out the jazzier side of a popular vocalist, (think Elkie Brooks, Helen Shapiro). Maxine’s first love was jazz and she loved to sing, but a hectic schedule while bringing up her daughter led to enforced rest in 1958, the first of several breaks in her career.

How does Maxine Daniels’ story link with today’s musical concerns? Why should readers care? Daniels was well-known in her day, admired for her straightforward approach to a song and ability to swing. As a black British musician, a foremother, she deserves to be remembered.

Many years ago, when I started documenting this history, I focussed on the Lynch family’s two singing siblings, the fourth and last respectively of 13 children, 10 of whom survived into adulthood. Hazel Daniels was helpful but knew little about her mother’s maternal line, having lived with her paternal grandparents during her mother’s illness. As for Kenny Lynch, an impressive jazz singer in his early days, he went on to carve out a show business career that saw him hobnobbing with characters as diverse as comedian Jimmy Tarbuck, former prime minister Harold Wilson, and, according to their friend Laurie O’Leary, the criminal Kray twins.

Manny Howard was my most useful informant. Born in 1923, the son of a Nigerian father and a mother of Polish descent, he grew up in Canning Town, in Crown Street, home berth for many black seamen. Willie Pell, an older boy, was his friend. Willie was a war baby, born in 1917, and an older sibling of Maxine (born 1930) and Kenny (born 1938). The Lynches were living in Crown Street at the time of Willie’s birth, but his mother became unwell and he was raised by Aunt Millie Pell, an older relative, born around 1875.

Aunt Millie, (née Amelia Spring), was living in Crown Street with Thomas Alexander Pell, a seaman from Antigua. In August 1919, she was an eyewitness to history. Racial resentment had been brewing in Britain following the First World War in which many black and brown people saw service. In 1919, attacks on people of colour took place in several major cities, an early precursor to more recent events. Pell was standing outside his house when a drunken white docker passed by and insulted him. When Pell laughed at the man, he was punched in the chest, and his windows and other property smashed. A number of black men were chased by a crowd that included several butchers armed with choppers and sharpening steels. Black men who fired shots above the heads of the crowd in self-defence were fined for having unlicensed weapons, but the white man was severely reprimanded by the West Ham magistrate and jailed. Pell himself made it into the history books.

Manny Howard told me about life in the small black communities in Canning Town, Stepney and Shadwell. His father, a devout man who came to England in search of a Christian life, arrived two years after the riots. He married and opened a café in Crown Street, taking in African and Caribbean lodgers. The family moved to Stepney, where Manny’s choices were complicated by his decision to opt for his mother’s culture. He attended a Jewish school, went to synagogue, and began to play music. West African lodgers had taught him piano, now he learnt guitar from others in his father’s Cable Street café. Eventually he led his own rock ‘n’ roll band as a drummer.

Armed, in part, with what Manny told me, I began researching the Daniels/Lynch family tree. Kenny died in 2019, his father’s Barbadian ancestry on record. Now Jamaica, too, was mentioned in the obituaries, but I was determined to link the siblings, through their mother, with an earlier, more complex, London history. Amelia Mary Ann Spring was born in 1895 of mixed heritage, with a mother of Irish descent. Those names continue to recur in this family; her third child was baptised Amelia, and then, of course, there was her Aunt Milie. Long before the days when the internet began simplifying such research, if not necessarily producing more reliable answers, I began trawling backwards through censuses, parish registers and vital records in search of connections.

On the 1851 census for Stepney, taken on 30 March, I found a sailor named James Spring, a British subject from the West Indies, born there 40 years earlier. He was living in Cable Street, married to Mary Ann Robinson whose racial identity is unknown. She was born in Southampton, around 1825 but her family were from East London, where they returned soon after her birth. As Mary Ann Spring, she worked as a laundress and had several children, the first around June 1850. She remains on the census for the next 40 years, described as a widow in 1871. Ten years later, she was sharing a house in Shadwell with another family headed by a West Indian, possibly her son-in-law. Other people of colour were living nearby.

Discrepancies in the census make it impossible to draw a direct line between James and Mary Ann Spring and any putative descendants, but I am pretty certain that this couple may be claimed as the maternal great-grandparents of Maxine and Kenny. Any Jamaican connection may be assumed to be through James Spring.

None of this was simple. Families were large in the past and deaths in childhood and infancy were common. There were errors on the part of census takers, and cover-ups when children were born out of wedlock. Babies and children were adopted unofficially and raised by other families, frequently leaving people unaware of their ancestry. Hazel Daniels received only the sketchiest information concerning preceding generations. Out shopping one day with her mother, they ran into a man named Uncle Bill. That’s your uncle, said Maxine, the same Willie Pell (né William Lynch) who grew up in Canning Town with Aunt Millie and Manny Howard.

Maxine Daniels made a number of popular singles before moving to Southend in 1963 and working with local bands. She returned to touring and recording around 1974 before taking another break from the music business.

In 1988, after recovering from heart surgery, she rejoined her old friend, Humphrey Lyttelton, who helped revive her career. She appeared at jazz festivals, worked in Holland with the Dutch Swing College Band and sang with a wide variety of visiting Americans, among them tenor saxophonist Al Cohn, cornettist Wild Bill Davison, and fellow vocalist, Billy Eckstine. She toured with the Pizza Express All-Stars and the Best of British Jazz, and recorded several albums and CDs for Lyttelton’s Calligraph label.

In the 1990s she toured with fellow singers Rosemary Squires and Barbara Jay backed by the Tommy Whittle Quartet, in a musical tribute to Ella Fitzgerald. She recorded for Spotlite (1994) and in 1996, worked with Barbara Jay and Tina May in a show entitled Ladies of Jazz.

Maxine Daniels died on 20 October 2003, remembered as a singer with jazz in her blood, and with a black British bloodline going back to at least 1850.

Thanks to Hazel Daniels, Manny Howard, Laurie O’Leary, Marian Wasser and Allan Wilmot

This article originally appeared in the October 2024 issue of Jazzwise. Never miss an issue – subscribe to Jazzwise today