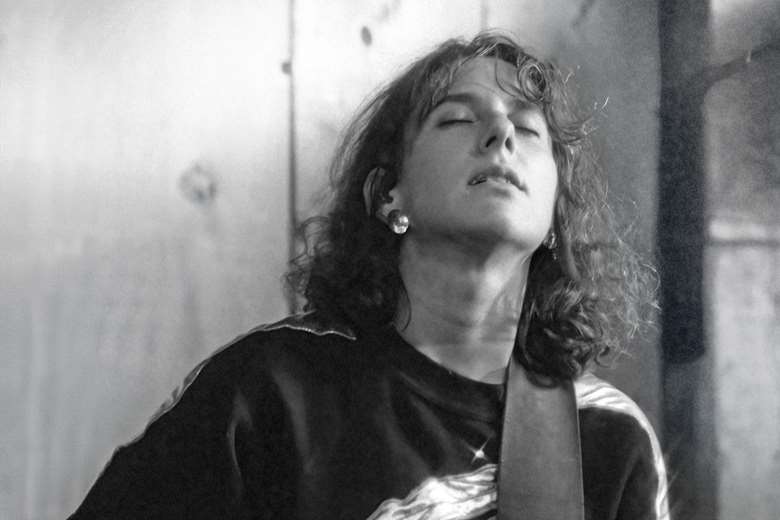

Emily Remler: The Queen of the Strings

Stuart Nicholson

Thursday, January 23, 2025

Stuart Nicholson remembers pioneering guitar maestra Emily Remler, whose early death robbed jazz of one of its brightest prospects

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Jazzwise.co.uk. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, live reviews and artist pages

- Free email newsletter