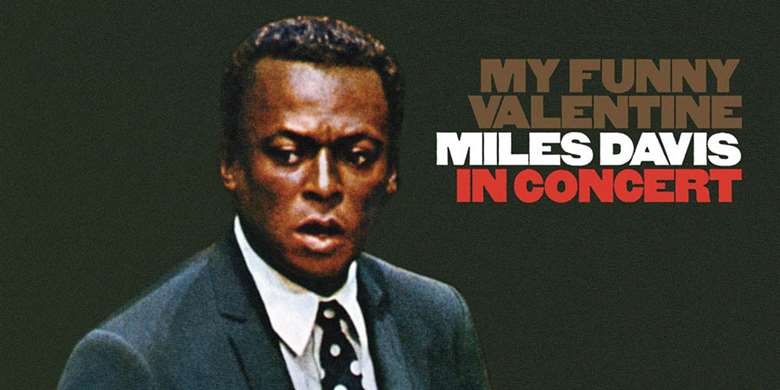

Great jazz solos: Miles Davis – My Funny Valentine

Tuesday, October 19, 2021

Brian Priestley unravels the magic of Miles Davis’ solo on Rodgers and Hart’s classic love ballad, nailing the song’s sentiments in five searing minutes of music

Almost nothing is known about Saint Valentine, but he never had it so good as when Larry Hart wrote his 1937 warts-and-all love-poem, ‘My Funny Valentine’. Listeners were blessed that Richard Rodgers set it to his simple minor melody – which he himself apparently persisted in regarding as a swing-bounce number like ‘The Lady Is A Tramp’, from the same Broadway show.

Perhaps that’s why it wasn’t a hit in 1937. But jazz-influenced, irony-conscious musicians gradually picked up on it, for example Mel Tormé in his 1947 radio transcriptions (Proper Records). It really came into its own the following decade, initially thanks to Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker. Their 1952 studio recording (Fantasy/OJC) preceded by more than a year the definitive vocal version by Frank Sinatra (Capitol) and, of course, it preceded Baker’s own vocal several months later (Pacific Jazz). According to Baker biographer James Gavin, it was Mulligan’s bassist Carson Smith who suggested using the tune, which was totally unknown to the other players.

That would give the lie to the assertion that Baker was playing ‘Valentine’ before he met Mulligan, but the tune does seem to generate its own urban myths. The tenacious one about Miles Davis (first printed in Bill Cole’s book) has him sitting-in uninvited with Max Roach and Clifford Brown in Detroit, doing the one tune and then walking out again with his horn in a paper bag. It was roundly disavowed in Miles’s own book: “I might have been a junkie but I wasn’t as strung out as all that.” What’s certain is that he did the tune on record four times – in 1956 with Red Garland (Prestige/OJC); in 1958 with Bill Evans; on 12 February 1964 for his live at Philharmonic Hall in Lincoln Center album My Funny Valentine; and five months later in Japan (all on Columbia).

And the greatest of these is the Lincoln Center version. Perfectly illustrating the creative tension of having his new band tackle his old hits, Miles turns his interpretation inside out, ditching the harmon-mute of his earlier recordings. Herbie Hancock’s out-of-tempo solo introduction creates such a mood that, when he holds his last chord and Davis plays the first six notes of the song, the atmosphere is already so charged there’s no hint of sycophantic applause. Miles soon departs from the melody, going way down and then running gracefully up the scale to a long held note, and yet there’s no accompaniment except for Hancock’s infrequent chords.

Then at 0’56”, which would have coincided with the second section of the song, Ron Carter starts adding sparse bass notes to imply a slow pulse. Miles’s very mobile phrases are mostly drawn from the song’s home scale, with telling injections of blue notes and bent pitches, but he still incorporates occasional references to the well-known melody – for instance at 1’17”-1’22” and at 1’37”-1’48”, the latter followed by a tension-filled pause filled by Hancock and Carter. In the last section of the song, starting at 2’00”, Miles returns with some repeated-note phrases implying double-tempo, but it’s not until 2’33” (equating to the lyric ‘Each day is Valentine’s day’) that an isolated high stab gives Tony Williams, who has so far been all but silent, the cue to start building a compelling groove.

As the quartet steam into a second chorus, Miles becomes far more active, using a wider pitch-range and greater rhythmic variety. (The extraordinary vocalised sounds at 3’44”-3’50” are another reference to the original song, and the phrase ‘Fav’rite work of art’.) But there is also much variety in terms of volume and energy, as in the relatively gentle section at 3’56”- 4’26” where Williams adds a simple Afro-latin rhythm, before reverting to the swing feel. The release of tension at the end of this section inspires Miles to hold the gentle mood for a few bars, before aggressively ascending to some of the most sustained high-register phrasing he ever achieved. Only after a gradual descent to his low register at 4’56” does Miles close in more relaxed manner, reverting to the kind of phrasing heard at 2’00”, and achieving a remarkable summation of his solo’s emotional trajectory and musical materials (Williams even hints again at his Afro-latin rhythm for a couple of bars).

The rhythm section reaches the start of the next chorus at 5’11”, but Miles continues playing as he backs away from the mike, repeating a three-note phrase that could be heard as saying “Follow that! Follow that! Follow that!” It’s true that, after these dramatic highs and lows, George Coleman has an impossible task to maintain interest for the next two choruses but Hancock’s contribution, curtailed by Miles’s return, is an adventure in its own right. It’s interesting that the Tokyo recording, with Sam Rivers replacing Coleman, is slower and rather shapeless, though Miles’s own solo occasionally recalls the electricity of his Lincoln Center performance.

Ian Carr’s book shows how that performance looks on paper (Ian’s transcription, my calligraphy) and tells us that, “Miles Davis had taken the technical and emotional exploration of standard song structures as far as was possible before they disintegrated completely and metamorphosed into something else.” Listen to it again and marvel.

This article originally appeared in the February 2014 issue of Jazzwise. Never miss an issue – subscribe today