Hermeto Pascoal interview: “Our bodies are resonating, we humans are a source of sound”

Kevin Le Gendre

Tuesday, May 24, 2022

Now aged 85, legendary Brazilian composer and multi-instrumentalist Hermeto Pascoal’s energy remains undimmed. Kevin Le Gendre spoke to him…

By way of information technology a laptop screen of today can suddenly become a picture frame of yesterday. In an unexpected moment during a zoom conversation with Hermeto Pascoal, the legendary Brazilian composer whose music is unique, and whose concerts are events, an image appears on the desktop that is quite astounding.

Even seasoned celebrity-watchers in the jazz world who think they have seen just about every shot of their heroes might blink. The man in focus appears to be dancing.

“This is Gil Evans at SOB’s in New York, 1985, ” says Pascoal’s designated translator, Jovino Santos Neto, a pianist-woodwind player and longtime member of his band, who pulled the snap from his files. The sense of elation on the face of Evans, a central architect of the orchestral language of modern jazz, is clear. His smile would light up all of 52nd Street.

“Every time we played in New York, Gil would come to see us (here he’s a few feet away from Pascoal). Once we played together in Sardinia.”

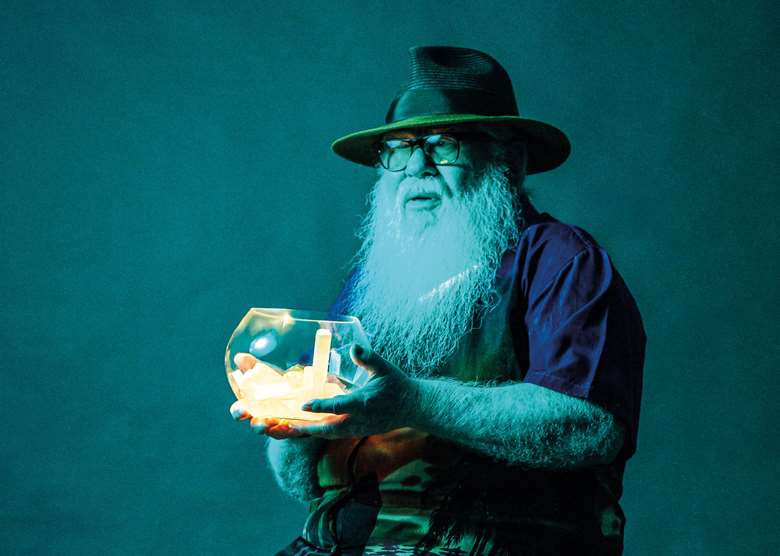

Hermeto Pascoal and his group (photo: Gabriel Quintão)

There was a wider mutual admiration society in operation here, as Pascoal had already won the confidence and admiration of the grand innovator with whom Evans was closely allied for long years, Miles Davis. The trumpeter’s 1971 album Live-Evil, which marked another of his key steps down the road of electric music, featured both the playing and writing of Pascoal, who fondly reflects on what he describes as “a big, deep spiritual connection” between the two jazz visionaries.

● Life-changing albums: Gil Evans’ ‘Into The Hot’

● Miles Davis and John Coltrane: Yin and Yang

● Eric Dolphy: Five Essential Albums

Which makes perfect sense when one considers that both shared a steadfast commitment to pursuing new directions in the world of sound, defying convention on form and content, searching for rhythm, theme and timbre that somehow goes beyond genre. Samba, jazz, folk, classical and avant-garde inventions are heard in Pascoal’s music but they do not define it. His ultimate motivation is to be entirely free of any notion of category.

“It’s been like this since I was a child,” says the 85 year-old multi-instrumentalist, from his home in the Jabour district of Rio De Janeiro, his wizardly white beard practically filling the computer screen. “Being a completely intuitive musician and not learning music theory until I was in my 40s, I feel a lot more than I think about music.

“When people hear my music they find it very hard to pinpoint and to pigeonhole it. When they think I am doing one thing I am already doing something else,” he notes in a low, balmy purr. “It’s very liquid, I’ve also played all kinds of music...in clubs, with dance orchestras… the musical environments for my work have always been very wide.”

Making his professional debut in the mid 1960s, Pascoal helped to broaden the vocabulary of bossa nova through his work with legendary Brazilians such as Edu Lobo and Quarteto Novo, alongside drummer-percussionist Airto Moreira, who later introduced him to Miles Davis. Pascoal then continued to develop as a solo artist.

For the past half-century he has been a seasoned international musical traveler who has dazzled audiences at prestigious jazz festivals such as Montreux and also collaborated many times with musicians around the world. Pascoal’s influence on several generations of European artists has been significant and in 2011 he led a big band at London’s Barbican centre that brought together his own ensemble and a host of leading British players. Next month, Pascoal returns to the venue on 5 May with his sextet augmented by the National Youth Jazz Orchestra, and the Norfolk & Norwich festival.

The concert features a world premiere of a new piece ‘Juvenal’, the nickname he gave Jovino years ago, as well as music written in the 1970s, 80s, 90s and 2000s. Pascoal’s musical DNA is stamped on the songs, providing the spark that made Gil Evans' face light up back in time.

When people hear my music they find it very hard to pinpoint and to pigeonhole it. When they think I am doing one thing, I am already doing something else

“I can safely say there is no big band arranger that writes like Hermeto,” says Jovino. “As I’m translating for you, I’m also doing that on a musical level by preparing charts for NYJO. They’ve been rehearsing and I will come to London a few days before the gig to rehearse in person. It is like a big conversation between Hermeto’s group and the orchestra, with Hermeto in the middle.”

If the visual image of Pascoal as a bridge between different ensembles is a strong one then it has a very provocative parallel in his music. His ability to juxtapose extremes of density and levity, speed and stillness, runaway rhythm and restorative melody, so that his writing is like a shifting landscape in which Afro-Brazilian, African-American and European traditions become one, has yielded a peerless discography.

Albums such as Hermeto, Planetario De Gavea, Slaves Mass and Cerebro Magnetico are startling examples of how a composer can exercise extreme attention to detail in his work all the while retaining the kind of spontaneity that flows from an equally gifted improviser.

Yet if Pascoal’s songs evoke anything from the flurrying intensity of a whirlwind to the tranquility of a mountain stream then he has an interesting view of the planet as a source of musical inspiration. He was born and raised in Lagoa De Canoa in Alagoas, a ‘federative unit’ in the north east of Brazil mostly known for its production of sugarcane and livestock economy, and in his formative years Pascoal spent a lot of time in the great outdoors. Today he does not see an irreconcilable divide between all things rural and urban.

“Nature does not mean only unspoiled things away from human influence, there is a similarity of sounds throughout different places,” says Pascoal with calm authority. “For example, I grew up in a very rural area with no electricity, no radio, no records, no telephones. But then when I went to the city in the north east and later Rio and São Paulo, I found that there was a big connection I could actually hear. I loved it when I heard the sound of automobiles, because for me it was like hearing the sound of cows.

“Now when I go back to nature, to the hinterland, I still feel like the city is also there, so these things that are not so separate. On one hand they are but they are also similar. I try to translate from one to the other,” he says, offering a neat summary of his ethos.

"They are similar but not the same. It’s important to enjoy the uniqueness of each place where we are. We’ve done gigs in industrial places with aluminium pipes, we’ve done gigs near a river or in a cave. So nature does not just mean a place that is the countryside. For me, all is sound… there are references everywhere I can use.”

Without pausing for breath, Pascoal further illustrates his argument with an imaginative allegory that has Jovino rocking back and forth with laughter before he goes about finding the adequate English words in order to share the joke.

“If I’m walking down the street and I bump my toe on a rock it might hurt my foot, but if that rock hits another rock then it’s a good sound. You pick up the two rocks and they suddenly become something new. That’s how I feel connected to the whole universe.”

Unity of humanity, ‘oneness’ through sound, has clear links to the credo of John Coltrane, but as much as Pascoal may be on similar conceptual ground there is a major difference between the two insofar as his life’s work hinges on several rather than a single instrument. He is a virtuoso on range of devices, from the accordion – so closely associated with the forro tradition of north East Brazil – to piano, flute and saxophone.

Seeing Pascoal in concert is exhilarating because it is impossible to know what he might do at any given moment. Yet there is not a dilettante’s self-indulgence in his movement from one ‘axe’ to another on stage, and his choice of what to pick up and play reflects a desire to maintain creative stimulus for both himself and his audience.

“Having all these different instruments is like being at a fruit stall with a lot of different fruits,” he says with a warm tone. “I can choose one or another and even if I play the same one again it is already something different, with a different flavour. This is the quality that I call universality… it has to do with creativity and spontaneity, and being able to face the music without having any pre-set objectives.”

That openness has repeatedly led Pascoal to investigate uncommon sonic territory. Sundry objects from toys to bottles of water, filled to different levels to produce a range of pitches, to animals to his own anatomy, have been used in his music, which extends the age-old, hugely democratic practise of handclapping found in many cultures around the world.

He has made a DVD of music created entirely with the use of his heartbeat, limbs, belly and beard.

"Humans are a source of sound. The tone of people’s voices is like music,” says Pascoal. “Our bodies are resonating, and we are able to transmit something by the sound we make with our whole body.”

To a certain extent, the statement is Pascoal’s creative life in a nutshell. The musician is the music regardless of whether they are using what might be deemed conventional or unconventional instruments. The crucial pre-requisite is imagination and an ability to tune into oneself and everything in the world.

Having observed Pascoal at close quarters for many years, Jovino is well placed to argue that the man known in Brazil as ‘O Bruxo’, the ‘sorceror’. has a sixth sense when it comes to identifying the musicality of what other people might deem non-musical.

“His ‘antennae’ are so well developed that he can capture things that for most people would be nothing. He can go to a country he’s never been to before and capture the vibration of the people, he has a very sensitive antenna for all kinds of things.”

Yet the rejoinder to this all too rare ability is an awareness of its limitations, of how the world of sound is elusive, if not fickle. As Eric Dolphy famously said, what we hear is instantly ‘gone in the air’. Pascoal has a similar outlook.

“Music is like the wind, a very sudden wind. It comes very quickly and you just have to be ready for it, and then it goes away,” he says. “That’s what I call universal music, it’s something that has that same fluidity; things can change so quickly, and that’s the way I respond. I can never predict what a concert will be like as I’m really living in that moment.”

This interview originally appeared in the May 2022 issue of Jazzwise magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today