Lyle Mays: A Personal Tribute

Adam McCulloch

Friday, February 28, 2020

An appreciation of keyboardist Lyle Mays, who died, aged 66, on 10 February

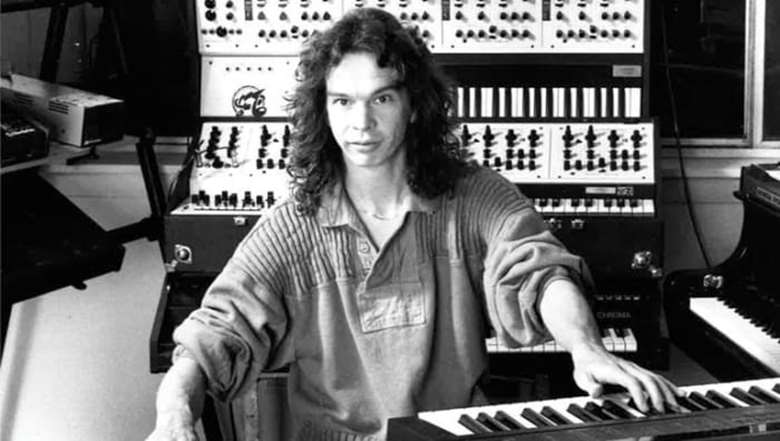

It was 1976 and I was in the cheap seats with my dad at the Royal Festival Hall for a concert by Woody Herman’s Thundering Herd. Strangely, the bottom dollar tickets got us a spot in the choir pews just behind the stage, giving us a close-up view of gods like Jim Pugh, Frank Tiberi, Alan Vizzutti and Dennis Dotson perusing their charts, wise-cracking, soloing, adjusting their horns. But nearest of all was a serious, tall, angular figure, his flowing locks right down to his hips: Lyle Mays, then in his early twenties.

Herman was keen to show off the young maestro, announcing Mays was fresh out of North Texas State University and prodigiously talented, before slyly adding to laughter from the audience: "Hey, kid, get your haircut". I don’t remember Mays reacting in any way, not even a faint smile. It was clear that he wasn’t a showbiz person and was totally in the zone, despite being a somewhat incongruous figure to be playing Woody’s old hits like 'Woodchopper’s Ball'. But even I – at the age of 13 – heard, as he built cascading, electrifying solos on more contemporary tunes like 'Spain', that this pianist was like no-one I’d heard on my dad’s jazz records. He was from another planet altogether and kickstarted my own journey of musical appreciation – I replaced Made in Japan and Queen II with Kind of Blue, Heavy Weather, The Romantic Warrior and, in 1978, the freshest sound of them all: Pat Metheny Group.

Fast forward to 1995 at the same venue and there was Lyle again, a sort of joint leader of the now mid-life PMG reeling off dramatic solos on 'First Circle', 'We Had a Sister' and 'To the End of the World' before a dazzling display of virtuosity on the extended intro to his tune 'Episode D’Azur' left the South Bank audience retrieving their lower jaws from the carpet.

Yet there was so much more to Mays’s musicianship than those dynamic piano improvisations delivered with a feather-sensitive touch. His signature synth patches – the ocarina-type sounds from his Oberheim and Prophet V – were totally identifiable as all his own and were a dominant part of PMG from the first album to the last. At later-life PMG gigs he would trigger midi sounds from the grand piano, to great effect on tunes like 'Song for Bilbao'.

For many of us, his collaboration with Metheny – and bassist/producer Steve Rodby – created an undefinable musical magic, yet while the band was Pat’s vehicle, there was always the sense there was more than one genius at work within it. In a rare interview a few years ago, with Jazziz’s Michael Fagien, Mays pays tribute to Metheny’s willingness to share the limelight: "Hats off to Pat for having the desire to have another strong voice in the music. His standards are so high and he’s so confident in his own abilities that he was comfortable having me in the band. Some bandleaders might have been intimidated by that. I really thrived on the collaboration and I think he did too."

This quote makes me smile as I recall the scene outside Shepherd’s Bush Empire after a PMG concert on the tour for the Imaginary Day album in 1998. Lyle emerged from a stage exit to be engulfed by a crowd of fans, one of whom cringingly demanded, "We want to hear more of you". Lyle doled out the usual thanks and headed for the waiting courtesy car.

I aspired to play improvised music with the same level of precision and attention to detail achieved by [Glenn] Gould playing Bach. That was an insane goal, because Gould could practice his parts; I was going to invent them on the spot. Aim high I say

Lyle MaysMays’ voice itself was not entirely that of a jazzer; he confessed his main musical inspiration resided in the work of composers like Stravinsky, Bartók and Ravel. And that was so evident in his compositions and the way he played: the brilliant on-the-spot reharmonising, the chord colours and sense of form. He told session keyboardist Jeff Babko: "I aspired to play improvised music with the same level of precision and attention to detail achieved by [Glenn] Gould playing Bach. That was an insane goal, because Gould could practice his parts; I was going to invent them on the spot. Aim high I say.'

His own, five, albums have aged well, but he told Jazziz that he didn’t feel there was a lot of demand for his own group and that good reviews didn’t really translate into good sales.

After PMG’s final record, The Way Up, which explored the full gamut of Lyle’s musical colours and tech wizardry, and the accompanying world tour through 2005-06, it seems he lost the appetite for life on the road. A final tour with PMG around 2010 marked the end of his musical involvement with Pat, who stated earlier this month: "It was clear in every way that he had had enough of hotels, buses, and so forth".

However, in 2016 a final record appeared; The Ludwigsburg Concert, documenting an exemplary quartet performance in Germany from 1993 that Lyle later said he’d forgotten had been taped. His long, structured and wildly evocative solos on 'Fictionary', 'Chorinho' and 'Hard Eights' are among his best recorded work and are essential listening.

As for the musicians who worked with him, and of course his family, there is a keener sense of loss, summed up eloquently by Metheny: "Lyle was one of the greatest musicians I have ever known. His broad intelligence and musical wisdom informed every aspect of who he was in every way. I will miss him with all my heart."