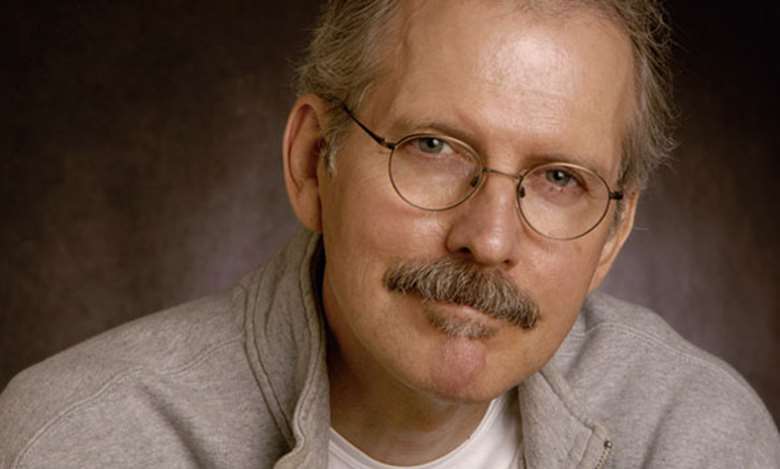

Michael Franks: free spirit

Thursday, May 9, 2019

David Pearson looks at the career of Michael Franks, a songwriter who has always followed his own path If ever an artist deserved to be far better known in Britain, it is surely American jazz singer/songwriter Michael Franks.

In a career spanning over 46 years he has released around 18 albums of self-penned material, not including compilations and Best Ofs. Yet he remains largely unknown to many British music fans.

Growing up in southern California, his parents were not especially musical. But he grew a liking for swing music. Aged 14 he bought a cheap guitar and a handful of private lessons, which turned out to be the only musical education he would have. He studied English at university and developed a love of poetry. And it was during a spell of part-time teaching work that he started writing songs, creating an anti-war musical as well as composing music for various movies.

I asked Michael what triggered his songwriting. "I wrote poetry at university and published a few in little literary mags. I turned to songwriting as my interest in music intensified. I played in a few different bands. At UCLA I met a pianist who was a real jazzhead and he literally taught me how to play standards. I had always admired the great American songwriters: the Gershwins, Cole Porter, Johnny Mercer, etc. So, all through my undergraduate years I worked at little clubs singing standards."

"If you listen to the earliest versions of some of the great standards, sometimes you wonder how they survived the test of time"

And these songwriters were major influences for Michael - "If you listen to the earliest versions of some of the great standards, sometimes you wonder how they survived the test of time. And I think the reason is that over the years they were lovingly embraced by jazz musicians, who continued to reharmonize and reinterpret them".

He began his recording career on the small Brut label before signing with Warner Brothers, with whom he would have a long relationship. His debut for the label was The Art of Tea (1976) and would yield a minor hit with the catchy "Popsicle Toes". His love of Brazilian music and rhythms, a strong element throughout his recordings, was evident in 1977's Sleeping Gipsy, with songs like "The Lady Wants To Know" and "Down In Brazil".

"At the same time I was working in this jazz duo, the early Jobim tunes were overwhelming the airwaves. So my partner and I included some of the obvious ones in our set. When I first heard Brazilian music I felt I had discovered a new land. The rhythm was so appealing and the melodies seemed to meander along, then make unexpected changes."

Franks relocated to the east coast and continued his recording and performing activities, often playing the cabasa when not on guitar. A minor chart hit came in 1983 with "When Sly Calls (Don't Touch That Phone)" from his Passionfruit album.

A major influence was Antonio Carlos Jobim, with whom he collaborated for a spell. He penned "Antonio's Song" and others in tribute to the Brazilian composer. Franks recalled the genesis of his love for the bossa giant and Brazilian music in an interview with Lee Mergner for Jazz Times:

"As soon as I heard that Getz/Gilberto album I couldn't get enough of it…I went to Jobim's apartment with Bill Evans. Jobim was incredibly nice."

And Michael treasures the memory of working with Jobim in his apartment, of the great man getting up to get coffee or something and humming "Popsicle Toes" from that first album - "And that was the ultimate compliment! To hear somebody like that walking down the hallway and humming a tune that he had just heard."

And Jobim's death in 1994 resulted in the Abandoned Garden album the following year, which he dedicated to the Brazilian composer. But there were other Brazilian artists Michael admired: "I recently had the pleasure of meeting and spending some time with Ahmad Jamal. He was a huge influence on me, like an education almost. Also, the Dave Brubeck records, Time Out and Time Further Out. Thanks to his sons, Dave got to hear the song of admiration I wrote about him and the quartet, "Hearing Take Five".

Over the years he has used some of the finest session musicians, arrangers and jazz players, including Joe Sample, Chuck Loeb, Larry Carlton, Michael Brecker, Wilton Felder and Steve Gadd, as well as singers such as Astrud Gilberto, Peggy Lee and Veronica Nunn.

His songs have been covered by many artists, including Diana Krall, The Carpenters, Natalie Cole and Manhattan Transfer. And in 2004 the English singer/songwriter Gordon Haskell released a whole album of Franks songs under the title The Lady Wants To Know.

Over the past 15 years or so Michael has adopted a more leisurely pace and has spaced out his albums, just 4 in that period, the last being 2018's The Music In My Head, which features Michael on piano as well as guitar:

"I think it just takes longer to be content with what you do. I enjoy it just as much - more - than I ever did. But I think maybe it's just a natural evolution. I know people think that I repeat myself, and I probably do, but I try hard not to."

The Music In My Head has 10 tracks with 5 different producers, including Gil Goldstein and Jimmy Haslip. This practice can sometimes create an inconsistency across an album but not here, and that's largely down to the sensitivity these guys bring to Michael's voice and style.

The opening track is “As Long As We’re Both Together” which Chuck Loeb arranged and produced, as well as playing guitar and keys on. His gorgeous guitar backing is a wonderful tribute to a musician who was to die soon after from cancer. In another song he recalls his early jazz club days ("Bebop Headshop"). And his deep love of the natural world is evident in "The Idea Of A Tree".

Reviewing the album for London Jazz Times Peter Bacon declared "It’s all here: the simply put, perfectly natural sentences, uttered in a gentle, matter-of-fact conversational style, a sort of speak-singing, as if the mood is too relaxed, the breeze too balmy, the sun too warm to go to the effort of really stretching those vocal cords; the rhythms are variations on bossa nova, the piano given the soft pedal, the guitar solo honeyed in both tone and phrasing, the saxophone tastefully sensual, the signature sound is the cabasa."

And Michael regards this album as "maybe the most autobiogaphical one I've ever written. It describes where I live, how I write, what inspires me."

Michael's music is often categorised as smooth jazz, a label he doesn't especially like, referring to it as a "euphemism". He doesn’t really have a favourite album, but I asked him about a favourite song? "Maybe that would be "Antonio's Song." (from the Sleeping Gipsy album) After all these years it still casts a kind of spell on audiences."

Always very modest and unassuming Michael Franks recalled a gig in New Orleans, during which he overheard an exchange outside the theatre between the venue steward and a passerby who asked who was playing that night - 'I don’t know,' said the steward. 'Some old jazz guy'. That appealed to Michael: "That was so great! My wife made that as a logo and hat for my birthday."

And in a web message to his fans some years ago he acknowledged the place of music in his life: "Music propels me toward the future. In a wonderful and miraculous way, it’s always whispering to me and circulating inside my head. I suppose, in that sense, I’m always writing."