Mike Westbrook interview: “You have to adapt to situations ... you have to find something that works NOW!”

Stuart Nicholson

Monday, May 23, 2022

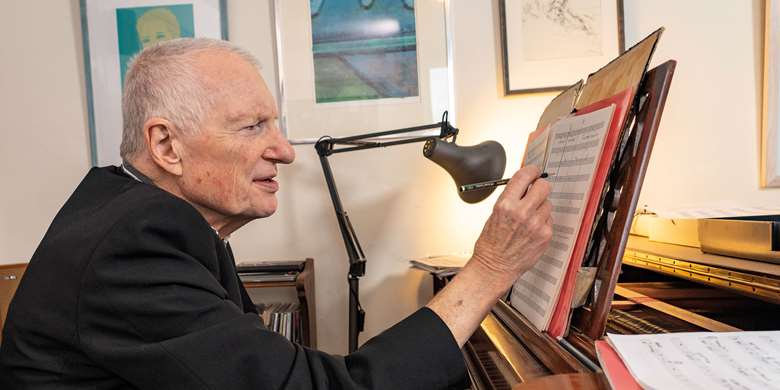

Stuart Nicholson speaks to the still-energetic 85-year-old Mike Westbrook about his poetic past, present and future

Life passes at an agreeable pace in the picturesque town of Dawlish, situated on the southwest coast of England. It’s as far removed from big city life as can be imagined, its tranquility once attracting literary greats such as John Keats, Charles Dickens (who used the town as the birthplace of Nicholas Nickleby), Jane Austen (who mentions the town in Sense and Sensibility), John Betjeman. That was then, but even now the town's historians are yet to acknowledge a bona fide jazz great has been resident in their midst for the last couple of decades. Not that it troubles Mike Westbrook, who has long become inured to the lack of honour bestowed upon prophets in their homeland.

Recognition for his formidable composing and arranging skills has not been in short supply, however. The degree of approbation he enjoys in Europe has long been a source of inspiration and – more particularly for a working musician – gainful employment. Now in his 85th year, he seems to have the energy and inspiration of someone half his age. Currently, he’s part-way through a series of events to celebrate a lifetime of achievement, including two nights at Ronnie Scott’s in April, and the Cheltenham Jazz Festival in May performing On Duke’s Birthday with his Uncommon Orchestra in what will be the first UK performances of the suite for big band – the work was originally recorded on 12 May 1984 at Le Grand Théâtre, Maison de Culture in Amiens with an 11-piece group.

“Playing Ronnie’s, it was possible to mount a new work there, you didn’t have to wait for a commission, the space was available, so just get on with it” – Westbrook on playing Ronnie’s in early days

“In 1983 I was commissioned by two festivals in France – La Temps du Jazz, Amiens and Jazz en France, Angouléme – to write a new piece to mark the then tenth anniversary of Duke’s death – he died in 1974,” recalls Westbrook. “‘On Duke’s Birthday’ is derived from After Smith’s Hotel, [a 1983 commission from Snape Maltings, as was ‘East Stratford too-doo’], but ‘Checking-in at Hotel Le Prieure’ and ‘Music Is’ were written especially for what was then a new line-up – two trumpets, trombone, Kate [Westbrook] on tenor horn, one saxophonist, Chris Biscoe, who plays all the saxophones, plus cello and Dominic Pifarely on violin. So we rehearsed, went to Amiens, and it was one of those great nights – you can hear it on the album, a miraculous coming together, all the combinations worked, the idea of only having one saxophone but using the cello in the section, and so on. I feel it was one of the best things I’ve ever done, really, a big success in France, where we played it quite a lot.”

Mike and Kate Westbrook (photo: Tim Dickeson)

Westbrook’s 85th birthday year also included a performance of what the Independent on Sunday called “Perhaps the greatest work in all British jazz” – 'The Westbrook Blake', settings of the poetry of William Blake. Performed at the Cadogan Hall as part of the London Jazz Festival in 2021, it was among a number of events that had been planned by the Westbrooks and their perspicacious manager Peter Conway for a series celebratory concerts, as Conway reflects: “I spent many months planning Mike’s 85th birthday celebrations. I managed to persuade some of the key players in jazz – Serious, Ronnie Scott’s, Pizza Express Live, Cadogan Hall, Jazzwise, the London Jazz News and the incredible Airshaft Trust – to collaborate on a six-month programme of major concerts to celebrate Mike’s achievements. I then approached the Arts Council of England and requested a small grant of £15,000 to bridge the gap between earned income and expenditure. They turned us down! Compare that to Italy, who are currently committing up to €30,000 to bring Mike and his 20-piece orchestra to re-open the opera house in Lugo with his Rossini Re-Loaded masterpiece on 6 October 2022. Mike is one of the few UK jazz composers lauded throughout Europe, but seemingly not in his country of birth – a somewhat shameful situation!”

“One had to be very strong in one’s convictions to question American orthodoxy and to work on developing an independent voice”

So it’s worth reminding ourselves that even in the broad church that is jazz, Westbrook has created a musical legacy of Brobdingnagian proportions that makes the word 'eclectic' appear narrow and limiting – his projects down the years have frequently involved his wife Kate, a talented vocalist, instrumentalist and lyricist in her own right – embracing brass band music, jazz-rock, street band music, The Beatles' repertoire, music for theatre, alternative theatre, dance and jazz cabaret, music for TV and cinema, opera, free improvisation, standards, jazz and poetry, composer tributes, such as currently, the music of Friedrich Hollaender, string quartets, and music for choirs and symphony orchestra – written for every permutation of instruments known to man, from solo through duo, trio and the whole kit and caboodle up to symphony orchestra and choir. Yet for many, the big band environment is where Westbrook’s musical personality assumes its sharpest definition. Currently, his latest big band, The Uncommon Orchestra, dates from the time he first moved to Dawlish. Comprising largely musicians from the West Country, plus one or two names long associated with Westbrook’s music such as Alan Wakeman, Chris Biscoe, Phil Minton and Dominic Pifarely, its humble beginnings belie its mighty roar.

“When we started living in Devon I asked around and formed a little band,” explains Westbrook. “We appeared at local events, and most of the kids could play a few notes and I wrote arrangements specially for them, and they became quite good and then quite professional and after a while I thought it would be interesting to play some of my big band arrangements, which were just rotting on my shelves, you know! So I thought okay, we asked around, and lo and behold, got together a big band of musicians locally which included Dave Holdsworth, who had moved down here, the late and much-missed Lou Gare, who was also living in Devon, alongside people who were still in school and we created this sort of family! We met in a pub, played and everybody enjoyed it, so it went on from there. We rehearsed a lot, everybody was very dedicated, and after a while we started doing gigs, and there has been a great continuity of personnel, people have stayed with it, really. It’s a wonderful band to work with, because I much prefer the trial-and-error approach – try ideas out and discuss it with people and eventually arrive at something that is sort of a consensus, and that progressed to the point where we are now doing major gigs!”

Westbrook first came to prominence during the 1960s and early 1970s, a period that has become known as the 'Golden Age of British Jazz', when the arrival of a number of exceptionally talented young musicians brushed aside the then prevalent belief that being American was a pre-requisite to playing authentic jazz. It was a time when British jazz was considered a pale imitation of “the real thing” unless played in the American manner. These young musicians begged to differ.

As a pianist who was very interested in composition and arranging, Westbrook points out that at the time: “One had to be very strong in one’s convictions to question American orthodoxy and to work on developing an independent voice.” He soon emerged as a leader on the burgeoning London jazz scene, “With the opening of Ronnie Scott’s club there was quite a lot of interest in the British scene,” he recalls, “I had been running a band up to that point, but I still had a day job, still teaching, and during that period I mainly worked with my sextet – John Surman [baritone sax], Mike Osborne [alto], Malcolm Griffiths [trombone], Alan Jackson [drums] and Harry Miller [bass]. During that time at Ronnie’s you had Chris McGregor’s Brotherhood of Breath and my group [as house bands]. One did an awful lot of playing back then, tremendous enthusiasm. I also occasionally enlarged the sextet, which then became the Concert Band, and Celebration grew out of that. Playing Ronnie’s, it was possible to mount a new work there, you didn’t have to wait for a commission, the space was available, so just get on with it.”

Next came Release, followed by the impressive and critically acclaimed two volume anti-war Marching Song, premiered at the Camden Arts Festival and recorded in 1969; “A milestone in jazz composition,” said The Sunday Times, “Beyond any doubt the supreme achievement in jazz composition and arrangement to date,” said Coda magazine. It took him to the top of the composer’s category in the 'Talent Deserving of Wider Recognition' section of the 1969 DownBeat Critic’s Poll. And just to put that achievement in context, that year fellow 'TDWR' winners included Albert Ayler, Roland Kirk, Lee Konitz and Chick Corea. “This all built up to a composition called Metropolis (1971), and that was a period when everything was happening. I was one of the first recipients of an Arts Council commission, and I think I got five hundred quid, and I immediately gave up my day job and became a pro and promptly struggled financially, still do really. It was a wonderful band, but at the same time it was a watershed, it marked a point where it wasn’t sustainable to have a big band because Ronnie's Old Place had closed, where we had been resident for quite a long time, everybody was thrown back on their own resources.”

However, it is this body of work – Celebration, Release, Marching Song, and Metropolis – that Ian Carr declared, “emancipated British jazz from American slavery,” meaning British jazz had found a voice of its own.

In the brave new world of the 1970s, Westbrook became remarkably adept at adapting to the changing musical climate. “I kept going with a small group, I formed a jazz-rock group called Solid Gold Cadillac, and then I sort of fell into the realm of the theatre – I became very involved with Alternative Theatre.” In 1975, a commission from Swedish Radio resulted in Citadel/Room 315 for big band and John Surman’s baritone saxophone that Westbrook considers one of his major achievements.

“I had a period of hardly any work, I had a year on which to work on this piece, in many ways it’s an exceptional record which is down to John, he was on the top of his game. It’s very much about my early days together with Kate, about falling in love. But the big band was not characteristic of what my life was like at the time, it was work with the Brass Band project.”

By now, the Brass Band had become central to his activities in taking jazz into the community, “Trying to make it part of the daily lives of people, it was a good idea and everybody in the band felt the same way, and that really went on through the 1970s.”

During this period he received a commission to provide the music for the National Theatre’s Tyger, a musical inspired by the poems of William Blake. Ultimately, it provided the genesis for one of his most enduring works, The Westbrook Blake, “Tyger was my introduction to William Blake’s poems, and by that time I was working with Kate, and Phil [Minton] who started singing the Blake songs with the Brass Band, and we’re still singing them today – we took over the Blake material [I did for Tyger], basically, and added more songs, developed arrangements, and it’s been through various generations, different line-ups, it’s the one thing in the repertoire we return to.”

Westbrook’s marriage to Kate soon blossomed into a highly creative husband/wife partnership: “When Kate became involved in what we were doing,” continues Westbrook, “we became fascinated with songwriting, which took the form of settings of poetry or writing what we called jazz cabaret, a whole new direction seemed to open up. We’ve done a prodigious amount of work over the years, we tend to move from one thing to the other, just a constant creative struggle, thank God we’re in it together and we can help each other through the difficult times and so on, but share in the joys of this jazz life.”

The sheer number of small group albums they have recorded deserves a small volume in its own right, including work as varied as, Art Wolf, Goose Sauce, Platterback, and A Little Westbrook Music. Their current project together is Kate’s Granite Band – “It’s a very unusual lineup with two guitars, bass guitar, me, drums, saxophone and of course Kate. It’s quite a challenge, but I must say, cutting edge, an exciting new area for me, opening up new possibilities.” Throughout, however, Westbrook’s roots have remained in jazz: “I’ve always seen myself a jazz composer,” he says. Here, his legacy is one of astonishing over-achievement that would fill a substantial volume. But even skimming over the wave tops of such latter-day classics as, The Cortege, London Bridge Has Broken Down, On Duke’s Birthday, Chanson Irresponsible, The Orchestra of Smith’s Academy, Bar Utopia, After Smith’s Hotel, Westbrook Rossini, and The Uncommon Orchestra: A Bigger Show, plus the first jazz performance on the main programme of the annual Sir Henry Wood Promenade Concert programme at the Albert Hall – surely his highest accolade so far – came in 1992.

“Pompeo Benincasa and Marcello Leanza, very good friends of ours in Catania, in Sicily, where we had played various projects, amazingly offered to do a festival of just my own music – basically whatever I wanted to play. They came to London, we discussed it and I said, ‘Well, what I’d most like to do is get everybody together, not only the regular band, but a few guests and things like that', and their faces fell at the enormous cost of doing this. They went away and several months later came back, ‘Well, we’ve got the money!’ So then, a long period of preparation for three different nights of music! A huge undertaking.”

And a huge honour too, Kate Westbrook told Wire magazine’s Kenny Mathieson that her husband had been close to tears thinking about it. But in the best tradition of prophets without honour, no similar commission to date has been undertaken in the UK. But even if it was proposed, where in his busy schedule would it be fitted in?

“There’s always ongoing work with the small groups of one kind or another, and the big band, that carries on, and every now and again, in parallel with that, there’s been a major project of some kind. You have to adapt to situations and I think that’s what keeps us moving, really. It’s a response to the changing world, you have to find something that works NOW!”

This article originally appeared in the May 2022 issue of Jazzwise magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today