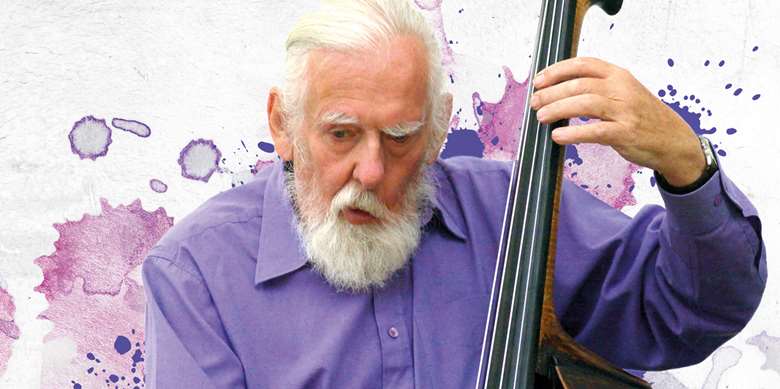

Peter Ind interview: “So few musicians really open their ears; they have preconceived ideas of where it’s at. They’re not necessarily right”

Nick Hasted

Monday, August 23, 2021

Bassist Peter Ind did it all. From playing with Miles and Bird, to befriending and teaching Mingus. In this, his final interview with Jazzwise, he reflects on a life less ordinary at the low-end of jazz

A couple of miles down the cliff path from Brighton sits the Sussex village of Rottingdean, once a roughhouse place of smugglers and farmers, now docilely picturesque. Behind one of its high garden walls, the now unfashionable, once lauded Rudyard Kipling wrote Kim. Behind another, close to the chalk cliffs, the English bassist Peter Ind is considering his own frustratingly unrecognised trail. He is 91 when we speak on two hot afternoons during this lockdown summer, long white hair and beard leonine and lifetime bohemian. The facial slippage of a stroke and husky whisper of his effortful speech signal the accumulated decades.

One could see him as a human equivalent to the Californian redwoods around Big Sur, where his post-war odyssey across America rested for a while, ringed and marked by fathomless experience. But as we sit in this peaceful place, with his Liverpudlian wife Sue Jones faithfully supporting him as she has for decades, the history Peter Ind has carried with him to this moment is of 1940s nights talking and playing alongside Bird and Diz, in New York’s legendary 52nd Street clubs as bebop was birthed.

“It was just, as a player, I wanted to be good. I wanted to be musically accepted. And eventually that happened.”

He was taught by Lennie Tristano and taught classical, high-necked technique to Mingus, played once with Billie Holiday and was on the Hickory House stand when Duke Ellington stepped up to jam. In the 1950s downtown loft scene, he saw Gerry Mulligan develop the sound he took west to conjure cool with Chet Baker.

But more than some lucky, characterless Zelig, Ind was an instigator. He knew Rudy Van Gelder when he was an amateur taper in New Jersey, and obsessively developed recording fidelity in his own home studios. He was Lee Konitz’s bassist for much of the 1950s, appearing on six LPs including The Real Lee Konitz (Atlantic, 1957).

Back in England, he opened the Bass Clef club in the then still bombed-out Hoxton Square in 1984, starting a regeneration of the area which ultimately helped close what had become a vital club 10 years later. His in-house studio recorded its music for his Wave Records label, adding to his vast store of tapes documenting the loft scene, his own experiments and the sounds of long gone birds and American trains. A trainee murmuration of starlings takes unsteady flight amidst constant birdsong now, in the idyllic spot where he’s fetched up.

But when I ask him to use his cellularly intimate knowledge of bebop titans, to strip away the myths and recall them as everyday flesh and blood, he is not inclined to play. If he pictures Charlie Parker standing just there, I point, feet away back at the Three Deuces club, what does he see?

“I’m listening,” he says immediately, as if absorbing the notes was all that ever mattered. “Oh, God,” Sue says, used to this stubborn insistence on seeing things his own way. “Yeah,” he protests, “but that’s where it’s at! I mean so few musicians really open their ears; they have preconceived ideas of where it’s at. They’re not necessarily right.”

Ind is more voluble in his excellent book about the milieu and music of his main mentor, Jazz Visions: Lennie Tristano And His Legacy (2005). “The feeling was of a special place – you weren’t there by accident,” he wrote of his first bebop immersion in the summer of 1949, the year Charlie Parker merged the music with strings at Birdland, which Ind found “outrageous, yet somehow beautiful and appropriate. And it was this quality that you could find in the jazz clubs of the time”.

He remembers the brownstone streets as quiet then, barely amplified music not carrying from clubland basements. And yet, as if in secret, the magic was being created right there. Playing bebop then sounds like joining an adventure.

“Yeah, yeah,” he says enthusiastically. “But you had to learn it. There were certain specifics, centred around certain phrases and approaches.” Ind was a bassist just as the walking bass style was being coined, grappling with radical shifts in phrasing emphasis, and learning to improvise on melodies when the melody itself had been spirited away; music college coursework now, revolutionary then. Discovering that Tristano taught music, Ind introduced himself to the blind pianist at a club, and studied at his Long Island home for years. Tristano taught the inner mysteries of scales till their whole architecture could be summoned in improvisation, and helped Ind’s English diffidence dissolve. It sounds like learning a complex foreign language, till you speak it like a native.

“Yeah, it was like that,” he considers. “It was just, as a player, I wanted to be good. I wanted to be musically accepted. And eventually that happened.”

Ind was born on the country fringe of London, in Uxbridge, Middlesex in 1928. Asthmatic and so often off school, with, Jones notes, a terror of a father who he’d avoid in rustic byways, it was a background to be escaped. Aged 14 he was playing swing to wartime servicemen in teenage dance bands. A photo with his friends then, all looking cheeky and keen, resembles rock wannabes two decades later. Drawn to jazz by Louis Armstrong and Glenn Miller, he was playing the fresh pop music of the day. “We were kids,” he recalls. “And when you heard that, it’s something else. So as a teenager, that’s where it’s at. It wasn’t initially clear I needed to go to America. It grew on me. Because Lennie had some recordings out, you could hear what was happening.”

A professional bassist by 1947, two years later he joined the likes of Ronnie Scott among the musicians entertaining on the transatlantic liners. First soaking up 52nd Street on a two-day stopover, and seeing everyone you could wish where you’d most like to see them – Coleman Hawkins at the Famous Door, and Erroll Garner, Bud Powell or Parker at the Three Deuces – in 1951 he moved to Manhattan. “It was the next step,” he says. He had already made his debut at the brand-new Birdland in 1950, casually invited to dep in Tristano’s band. Bird nodded his approval from the crowd when he played with Miles. He also visited New Orleans. “Just briefly,” he says dismissively. “I never saw it as the place of jazz. We were past that.”

He is drawn out a little on Billie Holiday, though not the rhythmic particulars of playing with her. “It’s just that I saw her as a great lady.” Dignified, then? “Not with me, he laughs. “She took no nonsense.” And Miles? “Rightly or wrongly, I didn’t value his contribution that much.”

New York jazz’s creative locus shifted to its downtown’s vast, chilly, cheap warehouse lofts in the 1950s, as 52nd Street was smashed up for skyscrapers. De Kooning paintings were on the walls of impoverished musicians and, when Ind had a loft of his own there in 1960, Allen Ginsberg was a neighbour. Wilhelm Reich’s orgone therapy tapped sexual energy, and air raid sirens early in the decade meant the Bomb always psychologically loomed. Ind taped this largely undocumented scene where he could, evidence released on later Wave LPs such as Lee Konitz’s Timespan (1977), and now being catalogued in Rottingdean. Ind’s own debut release with Tristano and Roy Haynes, the 7-inch single ‘JuJu’/‘Pastime’, included the first improvised overdub, with subsequent albums including Buddy Rich In Miami (a predictably wearing assignment in 1958) and Jutta Hipp At the Hickory House on Blue Note in 1956.

By the early 1960s, Ind’s parallel talent as an engineer led to sessions for labels such as Verve. Parker’s sudden 1955 death had already left jazz, as Ind had understood it, leaderless, even anarchic, allowing what he saw as a move away from pure improvisation. He was still more disconcerted by the racial politics, which the Civil Rights movement revealed. His engineering work on Max Roach’s We Insist! The Freedom Now Suite in 1960 brought this bafflement to a painful head.

“The music was changing, and the racial element came into it,” he says, a “cleft” which began for him in the early 1950s. “It’s like if there was a band, if you were a white bass-player, you didn’t get the call unless there was nobody else available. And recording Freedom Now, it was as though there were different vibes going on. Max apologised later, I think because he respected me. But the music was not just the music. It was the attitude towards it.” So when the Civil Rights movement became fundamental to many hard bop musicians on Blue Note and elsewhere, did it distract from what Ind entered the music for? “Yes,” he says emphatically. “What I find hard to take is how those attitudes... I never saw Bird like that. I think Mingus was more aware of race. But Mingus became a friend, and it was just about the music.”

Speak to the white in-house musicians who contributed to forging Southern soul at Stax Records in Memphis about their estrangement from black colleagues after Martin Luther King’s assassination, and Ind’s hurt and anger becomes less isolated. Not racist himself and participating in what initially seemed to him race-free art, the viscerally necessary stand Roach and others made against white repression felt wounding. Bill Evans leaving Miles’ quintet after Kind of Blue was one famous result of such ferment. Ind’s gravitation to, and preference for, Tristano and Konitz, is another.

Ind’s own debut album, Looking Out, compiled recordings including Sheila Jordan’s first in 1961. But though he’d thought he’d live in New York forever, in 1963 he abandoned its reduced jazz opportunities for Big Sur. Was he sad to leave? “Well did I leave?” he asks laconically. “Or did I just keep moving?”

His isolated house in this mountainous Californian coastal region was a difficult home for his first wife Barbara and their first child of two, though Konitz and Nina Simone’s musical director Al Shackman formed a shaky sort of scene. What Ind calls his “post-nuclear Impressionist painting” developed beneath its big skies. Quite different to Uxbridge? “You can say that again!”

Influenced by Reich and Van Gogh, the deep, variegated blues of his paintings’ skies seem to crackle and spark. The work is informed by deep ecological beliefs and, he suspects, his bass playing. “Even as a child I was aware of pollution,” he says. “But the only answer I had was to stop doing what we’re doing. And nobody did. Very few people take my painting seriously. But in a way it’s as important as my playing.”

How does he feel when he’s in the middle of either discipline, and it’s going well?

“When I’m playing and it’s going well, it’s like – look at that,” he says, and points to two butterflies dancing.

Ind’s American odyssey ended in 1966, when he returned to England. It seems to have been a period when he was always some sort of outsider, trying to find his spot. “I never found it,” he decides. “But what has been so difficult has been accommodating to England. It seems so narrow here. And what I found hard was that in England I was not really taken seriously.”

Initially put up at his parents’ Uxbridge home, Ind and his family were soon out in the wilds of Wales, then Twickenham. In 1967, he co-created the UK’s first full-time jazz course at Leeds College of Music, putting together the syllabus and teaching till he was forced out. Wave was revived and the Bass Clef opened, all of it promoting his devotion to an improvisatory ethic forged in bebop’s crucible.

There’s an unreflective, steely stubbornness to it all. “Whatever it was, I just did it,” he says of his path. The commercial requirements of success have been anathema. He recounts refusing to be taken on as a bandleader in the 1950s by major promoter George Wein and Louis Armstrong’s manager Joe Glaser.

“Little did I realise... that such an offer was unlikely to be repeated,” he writes in Jazz Visions, adding: “Born in the 1920s, the belief was instilled in me that success came merely with achievement.”

And yet, back in Britain, he found his extraordinary, hard-won New York experience now counted for little. Ronnie Scott was sympathetic, but his booking policies moved elsewhere. “I didn’t slow down,” he says of his response. “But it was like: why the fuck don’t they just listen to it?”

What did he think in the 1960s, too, when rock’n’roll stole jazz’s cultural thunder? “It didn’t,” he declares. But his contemporary notes, Jones says, show dismay. “Yeah,” he concedes of these changing times. “It’s weird. To me.”

Jazz students learn bop structures by rote now. But having learned from full immersion in the playing source, Ind now finds himself conversant in an almost dead language.

Only Roy Haynes and Sheila Jordan, perhaps, have been musically informed in the same first-hand way. It’s a rare tribe. Ind laughs appreciatively.

“Would you say you’ve stayed in aspic?” Jones asks.

“Yes,” he laughs. “Sometimes. Now, when did I become old-fashioned?”

Just as Ind thought he’d live in New York forever, did he think the secret magic in the clubs beneath its streets would be eternal too?

He nods. “And then it became apparent that it wasn’t – that it wouldn’t go on forever.”

It’s as if he discovered the secret of the musical universe, then came back home and no one cared.

“Yeah,” he says, voice rich with feeling.

“And yet it was real.”

This interview originally appeared in the October 2020 issue of Jazzwise magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today