The house that Ronnie and Pete built: celebrating Ronnie Scott’s at 60

Wednesday, October 30, 2019

From humble beginnings to iconic status, John Fordham charts the legacy of legendary venue, Ronnie Scott’s, which celebrates its 60th anniversary this year, and checks in with some of the key personalities intrinsically linked to this most celebrated of jazz temples

When those two deadpan romantics Ronnie Scott and Pete King opened a shoebox of a jazz club in a scruffy Soho basement in 1959 – bearing Scott’s name, because he was a poll-winning saxophone star of Britain’s tiny jazz elite at the time, and he was personable and funny enough to be the frontman – their ambitions just about stretched to renting a makeshift dive where they could play and share the music they liked, and making it through to the end of the week as long as the door-money held out.

That the two Eastenders went on to build a world-famous club that could survive six decades in the choppy waters of the jazz business was the by-product of a lifelong friendship forged in the sax sections of post-war London’s jazzy ballroom orchestras, in smoky rooms unpicking the mysteries of the 1940s bebop revolution, in smoochy ocean-liner dance bands, and in jazz banter and surreal gags swapped in battered buses on the road.

This 30 October, Ronnie Scott’s Club celebrates the 60th anniversary of its opening night. Sadly, neither of the original pioneers are still around to see their achievements being enjoyed afresh by music-lovers of all persuasions, backgrounds and generations – whether those fans might know about the club’s rollercoaster ride of unforgettable nights (from Sonny Rollins in his storming prime with local hero Stan Tracey’s trio to Jimi Hendrix’s last performance) and cliffhanging escapes from financial disaster, or whether they just happen to like the space, with its low lights, black-and-white photos of long-gone legends on the premises, and sense of idiosyncratic music being made and remade night after night.

That Ronnie Scott and Pete King were able to present so many stars within handshaking range of their eager punters could make a night at the club an unforgettable education, as well as a spectacle for fans and musicians alike. As the late John Dankworth put it on the BBC’s 1989 Omnibus documentary for the club’s 30th birthday (the same show on which Scott greeted that landmark with the suggestion that it was “like a prison sentence – 30 years in a jazz club”), the founders had proved that a Soho night spot could also be “a recital hall, a concert hall, a place of learning”.

Over the years from that Friday night in October 1959, some of the most influential figures in the 20th century’s most dynamic and diverse musical movement played the premises, at Gerrard Street from 1959 to 1965, and three blocks away in Frith Street from then to now – introduced in the earlier years, as like as not, by Scott as MC declaring: “Quiet please! You’re not here to enjoy yourselves.” There would be the great American solo stars who had risen in the 1930s and 1940s, such as saxophonists Ben Webster, Coleman Hawkins and Dexter Gordon, or the majestic vocal divas Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald. Maverick geniuses of an increasingly eclectic post-war jazz era came through, like Thelonious Monk, Sonny Rollins, Ornette Coleman, Herbie Hancock, Cecil Taylor and Bill Evans, the hard-bop drums firebrand Art Blakey (who first introduced a teenage Wynton Marsalis to London fans), Cool School spellbinders like Stan Getz, Art Pepper and Lee Konitz, and an influential doyenne of post-bop vocal ingenuity, Betty Carter. Even big bands could be crammed on to Frith Street’s tiny stage, including composer George Russell’s shapeshifting Living Time Orchestra, virtuoso drummer Buddy Rich’s showboating outfit, the South African-influenced Brotherhood of Breath, eclectic British trailblazers Loose Tubes (who in the 1980s brought with them a wider world-musical sweep that rejected jazz’s old sectarianisms), and Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts’ jazz-packed orchestra.

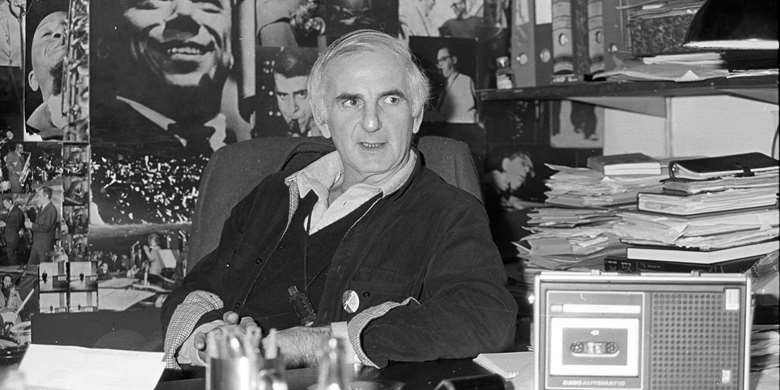

Ronnie Scott's in 1962

The club regularly showcased local heroes from Stan Tracey and Tubby Hayes to Gordon Beck, Norma Winstone, John Surman, Django Bates and many more. In a gesture of support in 1965 that older British artists have never forgotten, Scott and King donated the last 18 months of Gerrard Street’s unexpired lease to local players when the club moved to Frith Street, and the ‘Old Place’ saw the blossoming of a new generation of London musicians, notably in Mike Westbrook’s and Graham Collier’s bands, and among expat South Africans including saxophonist Dudu Pukwana and pianist Chris McGregor. In the early days, Scott and King had liked booking the former’s personal favourites (usually saxophonists), but as both jazz tastes and West End overheads changed they branched out – notably in later years into latin jazz, when they introduced Cuban pianist Chucho Valdes’ exciting genre-hopping Irakere ensemble to London (Ronnie Scott having made the first contact by playing at Cuba’s annual jazz festival) and established a perennial favourite with Frith Street audiences with former Miles Davis percussionist Airto Moreira and his singer wife Flora Purim.

And thus a remarkably durable formula by jazz-promotion standards evolved, one that survived near-bankruptcy over a neglected VAT bill in 1981 (a crisis rescued by five-figure donations from the Musicians’ Union and benefactors including Island Records’ boss Chris Blackwell), King’s major heart attack and recovery in 1988 – and even Scott’s sudden death at Christmas 1996, after which a grieving but determined King and the club’s sussed and loyal staff kept the show on the road throughout the next decade.

But retirement eventually beckoned for King (“look”, he reasoned to me in 2004, “I’m a 75-year-old man with the body of a 76-year-old – time isn’t on my side”), and after much heart-searching he sold the establishment to London theatre impresario and restaurateur Sally Greene and New Zealand-born theatre and music entrepreneur and energetic philanthropist Michael Watt, a jazz fan who had first visited Ronnie Scott’s back in 1960. Sally Greene quickly oversaw a stylish refurb of the club’s homely but by then neglected interior, but for the most part – after some early hiccups in establishing a management team with the nous to protect the club’s legacy but still keep it in business – the owners have kept their distance, and appreciated why Ronnie Scott’s and Pete King’s original vision mattered for over half-a-century, and still does.

By a mix of musicality, street-wit, and happenstance, the original founders created a very rare kind of music space – run by musicians for musicians, driven by a conviction that jazz was most fruitfully about the fast-changing perceptions of improvisers, who would flourish best when they and their audiences were in close contact. Moreover, it would be a place where performers attempting something different and surprising from night to night, rather than cloning their latest release, would feel like a privilege for those present rather than a disappointment.

Val Wilmer, the British music writer, photojournalist and Jazzwise contributor who began visiting the original Ronnie Scott’s in Chinatown’s Gerrard Street in 1960, recognised Scott’s and King’s lugubriously disguised virtues from the start. As a teenage jazz fan in the 1950s, she had realised that this young art was often made by people on society’s margins, who needed a special kind of empathy from their audiences and supporters. “Ronnie and Pete were a unique combination of personalities, with a great rapport for the music and the people who made it”, Wilmer recalls. “They might not always have been totally PC as we’d understand it now, and they could be outwardly rude at times, but they respected serious, creative musicians unquestioningly. Not only that, but they respected their audiences too, and people like myself who wanted to report on this fantastic music – people who were beneficiaries of what those artists were doing, and who were prepared to devote time and work to getting to know it better, when so many people didn’t appreciate it.

“I didn’t know anyone in the music business of those days as generous as those two men were to me when I was starting as a music journalist,” Wilmer continues, and coming from an unflinching challenger of powerful people’s presumptions, it’s a big compliment. “They weren’t always nice to everyone, because they could spot bullshit through a closed door. But they knew who was ‘family’, as they would call it, and who wasn’t. ‘Family’ would extend to musicians, famous or not, or even whether or not they misbehaved – like Ben Webster falling off the stage drunk, or Dexter Gordon floating in for his second set having missed the first – and Ronnie always made a point of name-checking every player in a band, from the star to a complete unknown. They’d also take care of musicians’ friends and relatives, often fix them up with a nice seat and a meal and a drink for the gig. No wonder they never made much money then. But they knew they had pure gold in the talents of the people they were bringing in. They also understood how important black musicians were to jazz, and employed black people as front of house staff when a lot of other employers in those days wouldn’t.”

The careers of both Scott and King had begun as dance-band saxophonists, fondly dreaming of a way to play nothing but jazz. Bow-born King played tenor in the bands of Jamaican trumpeter Jiver Hutchinson, popular 1950s drummer/composer Jack Parnell, and in Ronnie Scott’s groups of that decade, before moving into management and promotion.

Scott (born Ronald Schatt in 1927 in Aldgate, one of Europe’s biggest Jewish communities) was the son of a local shop worker called Cissie, and a Russian-descended saxophonist and bandleader called Joseph Schatt, who adopted the name Jock Scott. Jock Scott was a domestically evasive man, a keen gambler (imperfections his son would serially replicate) and an absent father from shortly after his son’s birth. But Ronnie Scott was drawn to his world of ballrooms, clubs, hot music, and racetracks in his adult years – even playing commercial jobs with Jock on occasion in his twenties, though they were sometimes uneasy meetings.

Ronnie Scott’s rise to British jazz fame was fast. He had been bought a gleaming Pennsylvania tenor sax by his mother and his stepfather Sol when he was 13, and within five years he was in the sax section of Ted Heath’s famous and well-paid orchestra. Heath eventually fired his sharp young recruit for trying to smuggle the flying runs and serpentine phrasing of the new bebop style into the orchestra’s sleek dancefloor sound. But bop was hip, new, and irresistible to Scott’s jazz generation, the luminaries of which included alto-saxophonist John Dankworth, trumpeter Jimmy Deuchar, and the drummers Tony Crombie and Laurie Morgan.

They took gigs in the transatlantic ocean liners bands as a cheap route to New York, soaked up the sounds of American revolutionaries including Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie over ecstatic nights club-crawling in Harlem, and in December 1948 launched their own London bebop joint, dubbed the Club Eleven. It ran for two years as a magnet for beatniks, hipsters and the jazz-savvy, until a drugs bust closed it in 1950.

A regular Melody Maker poll-winner, Scott was then diverted for much of that decade by leading excellent bebop bands of his own, culminating in the Jazz Couriers quintet he co-led with young tenor-sax virtuoso Tubby Hayes. But he had dreamed of a London jazz club inspired by 52nd Street’s The Three Deuces ever since those heady New York trips, and it was plainly still on his mind when he was interviewed by Melody Maker in autumn 1958 as “one of the post-war angry young men of jazz”. Scott wasn’t that angry, give or take a little sarcasm about the coming of rock’n’roll, but his hopes for the local jazz scene were clear. “I’d like to see a new type of jazz club in London,” he said. “A well-appointed place which was licensed, and catered for people of all ages, and not merely for youngsters.” When the Couriers wound up the following year because the 24-year-old Tubby Hayes wanted to spread his wings, and a Gerrard Street basement became available for a knock-down rent, the rest was about to be history.

“What Ronnie and Pete did with that opportunity, and the legacy they created, is something we’re constantly aware of in continuing to run a place with Ronnie’s name over the door,” says Paul Pace, a long-time stalwart of London jazz-promoting and record-shop life, and since 2009 part of the club’s management and programming team under former Jazz FM executive Simon Cooke. “We want to carry on the legacy, and raise the bar for it as high as we can. After Ronnie died, Pete continued to do the bookings on his own as he always had, but the demographic of the club’s audiences was getting older and perhaps there needed to be a bit more variety. I’m sure he knew something needed to change, and when he sold the club, he wanted it to be to people he felt would do that sympathetically. We feel that’s happening, and that by pooling knowledge and expertise across a five-strong music booking team of Simon, James Pearson, Nick Lewis, Sarah Weller and me, with all our different specialisms, hopefully we’re broadening out what the club offers.’

Over the past decade, life at 47 Frith Street has certainly speeded up. ‘The Late Late Show’, a regular after-hours event that might feature anybody from quirky unknowns to surprise visits by passing stars, has become a significant draw – Wynton Marsalis said of it, “we haven’t had anything like this in New York for 20 years”. ‘Upstairs @ Ronnie’s’, featuring a weekly jam session, has played a significant role in London’s jazz resurgence among young fans and players in recent years. Other nights in the bar on the first floor thrive, with live music events covering a wide range of genres from jazz, indie, alternative folk, New Orleans R&B to Cuban, except for a DJ night on Saturdays.

A now annual week-long festival devoted to the classic piano-trio format has brought together artists as different as American jazz/hip-hop superstar Robert Glasper and UK original Elliot Galvin, and pop-up gigs under the Ronnie’s banner in other venues, and high-profile club promotions at venues from Camden’s Jazz Cafe to Chelsea’s Cadogan Hall have further widened the net. Under Michael Watt’s guidance, Ronnie Scott’s has acquired charitable status for outreach projects and educational work, like the ‘Big Band In A Day’ project, in which young musicians rehearse for a day at the club and form an impromptu big band for a performance.

Would Ronnie Scott himself, and the bohemian Soho circle that embraced the club’s earlier years, have liked the revamped establishment’s marketing sharpness, and its glitzier contemporary style? Maybe not. But if Scott and Pete King were one-offs who thought the right music and musicians were all that mattered, far more of their original vision has been preserved by their heirs than they, or the world’s ever-evolving jazz community, might have feared.

If the secret of Ronnie Scott’s lies in any single place, it’s in the late frontman’s impulsive, gifted, contradictory character – a popular gag in the ‘family’ was that he was ‘a very interesting bunch of guys’. When I wrote two editions of a biography of him in the last decade of his life, glimpses of light were shone on that enigma during a number of meetings in the humdrum, instrument-packed back room behind the Frith Street club’s famous stage, with its permanently murmuring TV playing the races. Over time, the guarded Ronnie Scott opened up about everything he’d hidden from the public by deflections and gags – many transient and a few precious and profound relationships, his two children Rebecca and Nicholas, periodically debilitating depression and self-doubt, the frustrations of reaching sublime moments in a spontaneous music so rarely, but the certainty nonetheless that playing jazz on a saxophone was what he was on this planet to do.

I wrote in his obituary for The Guardian at Christmas 1996 that Scott seemed to hear in the “evaporating symmetries of jazz, an urgent tension between the perfect and the ephemerally mortal… most jazz lovers have heard a whisper of something like it.” Naturally, he put the secret of jazz – and the secret of the unique refuge for it he and Pete King created – more succinctly, in a conversation we’d had a few years earlier. The club “gave audiences a chance to see the players’ humanity,” Scott said. “That they could be wonderful – and that they could also fuck up, like everybody else does.”

This interview originally appeared in the October 2019 issue of Jazzwise. Never miss an issue of the world's leading jazz magazine - subscribe today!

Free Ronnie Scott's CD

The October 2019 issue features a very special Ronnie Scott's cover-CD – a journey through 60 years of the club – the issue is still available to purchase from Amazon