The inside story of Keith Jarrett’s iconic Köln Concert

Stuart Nicholson

Thursday, January 23, 2025

As the 50th anniversary of Keith Jarrett’s iconic solo improvised album The Köln Concert comes around on 24 January, Stuart Nicholson tells the story of the less-than-favourable conditions that surrounded its creation. ECM label boss Manfred Eicher and Jarrett himself also reflect on this 66-minute spontaneous composition that has sold more than four million copies

In 2009, the documentary 1959: The Year That Changed Jazz was first screened on BBC Four. The film focused on four major jazz recordings – Kind of Blue, Time Out, Mingus Ah Um, and The Shape of Jazz to Come – which the producers considered were head and shoulders above everything else released at the time. Portrayed as a watershed moment, for many viewers the unspoken subtext was that it’s been downhill ever since.

These recordings continue to be hugely influential and are regarded in jazz education – along with John Coltrane’s Giant Steps, also recorded in 1959 – as the foundation of contemporary jazz studies. But for some, there’s been a creeping realisation that other jazz recordings from a more recent past have also become classics – and without the need of a TV documentary to tell us so.

Everything was wrong. It was the wrong piano, we had bad food in a hot restaurant and I hadn’t slept for two days and we almost sent the recording engineers home

Keith JarrettOne such album is Keith Jarrett’s Köln Concert, the fiftieth anniversary of whose recording was on 24 January 2025. If the only indication of value was consumer demand, then this album would be up there on that alone. Of course, there is a lot more to it than that, but with sales figures of four million or more being bandied about you don’t have to wander too far into cyberspace to discover it’s synonymous with phrases such as 'the best-selling solo album in jazz history', 'the best-selling piano album of all time', and a 'core album for any collection'.

One of the many factors that have contributed to the album’s success was the mystique it attracted. Jarrett later said he experienced the concert as "an existential experience", and many listeners say they have felt something similar when listening to the music.

Here was spontaneous composition on a grand scale. There are sections of the Köln Concert where one melody leads to another, as if pre-ordained. Other interludes lead into essences and abstractions of other styles and other moods. No wonder when gazing into the heart of Jarrett’s 66-minute improvisation, the music yields a myriad of different meanings.

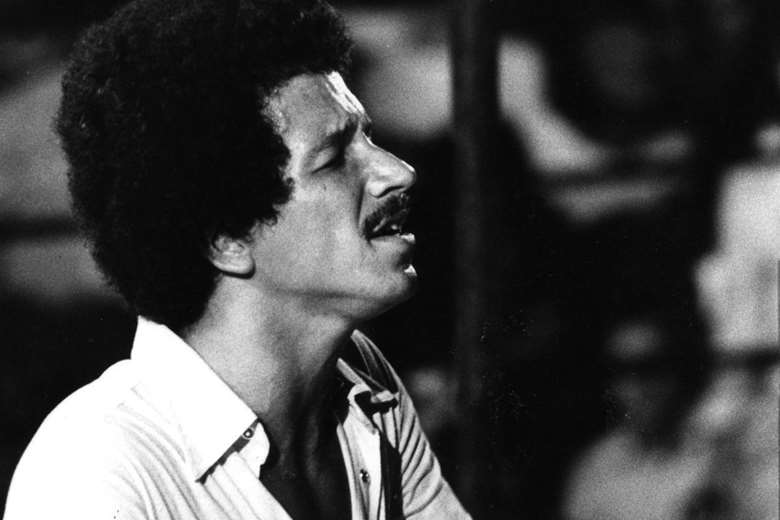

In concert, a picture of concentration and commitment

Rather like witness statements for an unusual happening whereby each participant describes the same event differently, so too with the Köln Concert. No two people hear it the same way. Some focus on the jazz content; others, the classical elements, such as moments evoking Claude Debussy or Sergei Rachmaninoff; still others talk of the folk, blues and even rock connotations they hear.

The unifying element is the album’s deeply spiritual feel;“We felt something special was happening,” says Manfred Eicher, who produced the record. “It did have some miraculous kind of quality, otherwise it would not have reached millions of people.”

Eicher’s independent label ECM – Edition of Contemporary Music – was founded in the then West Germany in 1969. Its initial release was Free at Last by Mal Waldron, which met with modest success and the recordings which followed, by the likes of Paul Bley, Jan Garbarek and Wolfgang Dauner, all played a part in establishing the label in the recorded music marketplace.

The label’s profile was given a boost when Chick Corea began recording for ECM: “Return to Forever was the first recording Chick Corea did [for us],” says Eicher. “We did it on a very limited budget [from ECM] in New York in a day, and then Chick Corea and I mixed the album in Stuttgart, and it became a very successful record.

"But you have to see it like this: until this record and until Corea’s Piano Improvisation No. 1 and Jarrett’s Bremen Lucerne, ECM’s records were not selling in big quantities; even Return to Forever did not sell in such incredible quantities at the very beginning – over the years it sold very well, but it was not really until 1975, when we were already six years in business, that we had the big success with the Köln Concert. One cannot really say we had to have this record to build up the company or the catalogue. The catalogue was built up from Free At Last and continued. But with the Köln Concert, people started to find out about Bremen Lucerne, about Facing You as solo records by Keith Jarrett, and started to buy them. They started to become aware that ECM was doing something different in this area. So there are many recordings that helped us do what we do right now that [helped] make us independent.”

Jarrett with ECM label boss Manfred Eicher (photo by Roberto Massotti)

The runaway success of the Köln Concert is all the more remarkable when you consider it was a concert that almost never took place, and even when it did, the album’s success was neither anticipated or planned for. The concert had been arranged for 11.30pm on 24 January 1975 in the Cologne Opera House by 18-year-old Vera Brandes, then Germany’s youngest concert promoter. She had a full house of some 1,400 fans who had paid 4DM a time, yet behind the scenes the omens for success were far from promising. The piano was out of tune, Jarrett was suffering from sleep deprivation, back pains and a stomach upset and was in no mood to walk onto an empty stage, and, as he put it, “Sit at a piano, bring no material, have no pre-conceived musical ideas and play something of lasting value and brand new.”

In January 1975, Manfred Eicher had arranged a series of solo concerts in European venues for Jarrett.

“We were driving to various concerts in a small R4 Renault which I had at that time,” says Eicher. After playing a concert in Zurich, Switzerland, Eicher and Jarrett set off on the long car journey to Cologne, where they arrived in the late afternoon tired and stressed.

Jarrett had failed to catch up on any sleep during the journey, but on arrival the overriding concern was finding somewhere to eat. When they did, they were confronted with a long wait, and to make matters worse, Jarrett’s meal disagreed with him – violently.

“In the afternoon he really felt like not doing the concert,” continues Eicher. “But we made the soundcheck and he was not liking the piano at all because we had ordered a Steinway Grand, but the day of the concert there was a strike at the supply company so the special piano that we rented for this occasion had not arrived, so he had to play with the rehearsal piano.”

From Jarrett’s perspective, the reasons for cancelling the concert were mounting. Physically he did not feel up to it, mentally he had the feeling he should not go ahead. Although the piano tuner summoned did his best, the piano had several notes that remained obstinately out of tune.

“But in the end he decided to do it,” says Eicher, who is at a loss to explain why or even how the album became the success it did: “The night it was recorded, everything seemed against a good recording,” he says.

Jarrett takes up the story: “Everything was wrong. It was the wrong piano, we had bad food in a hot restaurant and I hadn’t slept for two days, and we almost sent the recording engineers home. Manfred said, ‘Why don’t we record it anyway since they’re here?’

"But I knew something special was happening once I started playing. I remember going on stage thinking there’s no place I’d rather be than sitting at the piano – finally! Sometimes when your resistance is low ideas come, and the piano being a different instrument than I would normally play, I played it differently.”

Listening in the wings, Eicher, tired and jaded after the day’s events, suddenly became transfixed as Jarrett’s performance unfolded: “I think he was just in an incredible flight that night, he just played, forgot the piano, and played as he has never played before and never played again."

After the concert, he had a tape copy run off to listen to while travelling to the next concert: “As we drove, we played this tape over and over in the car and we felt there was something really special happening, but we were kind of irritated by the sound, and so Keith said let’s go in the studio. Later I did go in the studio, months later, and worked for three or four days on the tape and the result was actually quite remarkable despite the piano.

"The piano can never be retuned in a mixing session, however it seemed to be speaking to a lot of people and to a lot of famous sound engineers and this record won many awards – curiously enough some for the sound, and sometimes it’s a surprise to me why! We had no idea it would be so big, it just kept selling and selling and sales are now in excess of four million.”

It is a success story that cannot be divorced from the musical context of the times in which it was recorded, a time when the adult contemporary format was consolidating as a marketing concept as pop got mellow to the sound of Bread, The Eagles, Chicago, Fleetwood Mac, England Dan & John Ford Coley, James Taylor and the Carpenters. Rock fans chilled to the music of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells and Pink Floyd, whose extended compositions – ‘Echoes’, ‘Atom Heart Mother’ – could last a whole album side.

It was a musical milieu into which Jarrett’s accessible, yet challenging improvisations found an audience beyond jazz. In the late 1970s and 1980s, if you walked into a boutique, a wine bar, a bookshop, or a trendy restaurant, there was a good chance The Köln Concert would be playing in the background. It was music in tune with the times.

Then, as now, it’s an album that fulfils the function of both passive and active listening. The passive listener might regard it as sophisticated background music that provides an ambiance that might be appropriate for entertaining friends at home or making love to, but it is also an album that encourages active listening, where it functions as emotionally stimulating foreground music.

Anyone who has seen Jarrett in live concert will know what an emotional player he was. It was the centre of his art. His commitment to giving his all every time he played and the intensity of his expression was reflected in moans of anguish at the moment of creation that were often picked up on mic. It prompted one commentator to quip, “He sounds as if he is giving birth to a square baby.”

Looking back at the time when he concentrated primarily on live solo concerts, Jarrett reflects, “The amount of energy these concerts took was always amazing to me. It was like the Olympics each time.”

The lasting image of Jarrett the performer is of an artist so focussed on the creative act that the audience was excluded. If his train of thought was interrupted by a cough, a camera flash or a sneeze he was known, on occasion, to express his frustration with the audience. It was all contributing to the unique aura that began to surround a Jarrett concert.

In 2009 he explained: “Because I don’t bring material, I am responding to what kind chemical feel there is in a room between all the people sitting in the audience and me. They know they are commissioning a new work, really. They don’t expect to hear the Köln Concert again. I guess I’m lucky I started early enough that I can actually fill a hall with people who want to hear me. But to imagine my work is done excluding the audience is a mistake; and is a mistake audiences have made because I am sensitive to their foibles – all I want is their attention and some respect for the process, which means I can’t sneeze on stage either!”

Ultimately, The Köln Concert reflects a moment in time, a musical photograph at the beginning of Jarrett’s journey into the art and heart of the solo piano concert, an idiom he almost single-handedly popularised that led, in addition to The Köln Concert, some of his best-loved albums – Solo Concerts: Bremen/Lausanne, Sun Bear Concerts, Paris Concert, Radiance, The Carnegie Hall Concert and in more recent times, the previously unreleased La Fenice, Munich 2016 and Budapest Concert.

But the solo recordings reveal just one aspect of his wide- ranging musical achievements. If a moviemaker was to call for a slow pan across the entirety of his recording career, it would surely include his American Quartet, his Scandinavian Quartet, his Standards Trio plus collaborations with other musicians including Jan Garbarek and Kenny Wheeler, compositions and arrangements for string orchestra, such as Luminessence and his highly acclaimed ventures into classical music such as Dmitri Shostakovich: 24 Preludes and Fugues Op. 27.

When interviewed in 2010, I asked him how he felt about the album that was undeniably a landmark in his career: “I have a complex relationship with The Köln Concert,” he confessed. “I realise how, first of all, I didn’t play the piano nearly as well then, so if I listen as a pianist I hear these put-together-sections that are creating themselves, and there is nothing like it in the discography. It was a moment in time and I had the wrong piano and I don’t exactly like my actual touch, my dynamics at all, but there were ideas floating around in my head and I was young and it has these colours and voicings that at that time people were not playing.

"So what happens around the time of releasing an album has lots to do with how it was received, but in the here and now its life span seems to go on and on.”