Wayne Shorter’s final interview: “Through struggle and chaos, we find the elements for survival”

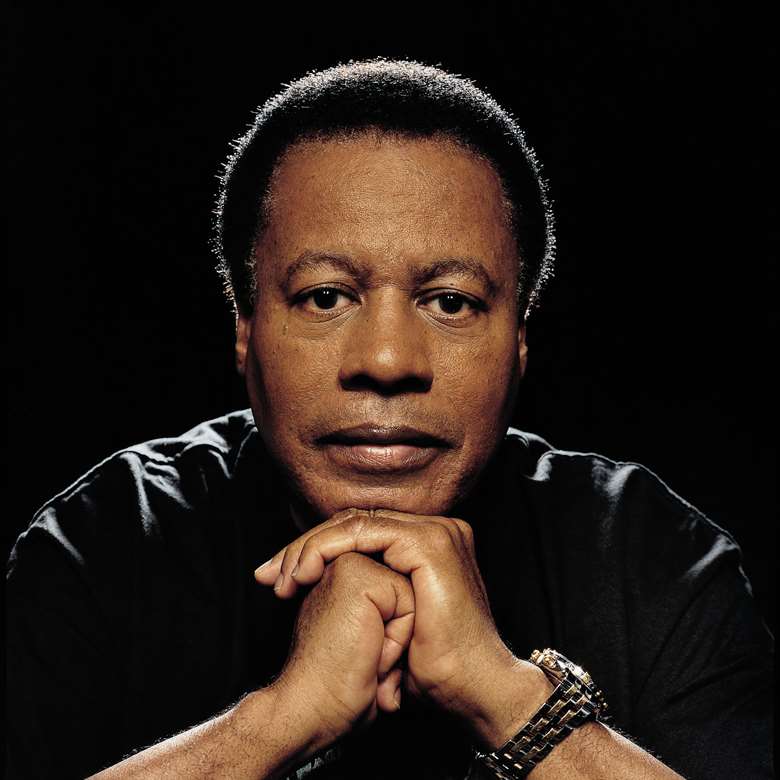

Michael Jackson

Wednesday, September 20, 2023

Late last year, renowned writer-photographer Michael Jackson spoke to Wayne Shorter at length, resulting in one of the great saxophonist’s last-ever interviews

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Jazzwise.co.uk. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, live reviews and artist pages

- Free email newsletter