Carla Bley: 11/05/1936 – 17/10/2023

Staurt Nicholson

Wednesday, October 18, 2023

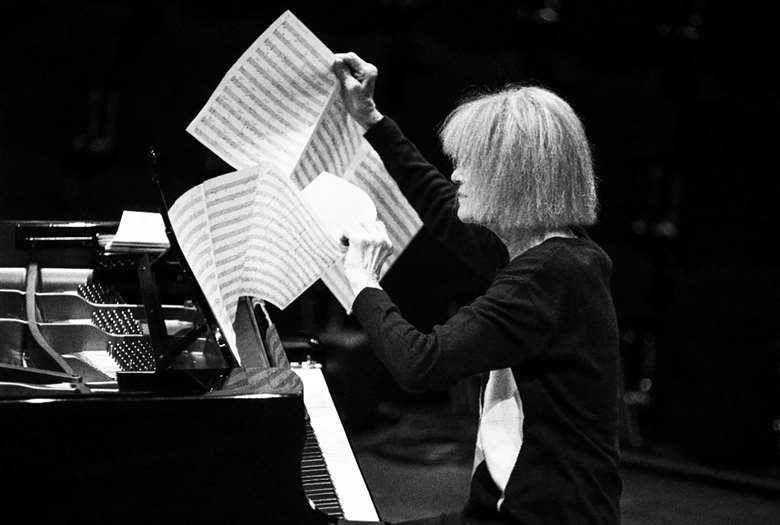

Stuart Nicholson remembers the iconoclastic, innovative and occasionally mischievous composer and pianist Carla Bley, who has died at the age of 87

Pianist, arranger and conceptualiser Carla Bley, who died on Tuesday 17 October aged 87, loved to laugh. She thought it hugely funny when, on her first tour Europe of Europe, the audience pelted her and her band with fruit and the occasional bottle. Delighted, she said she started throwing it all back at the audience, and as her band joined in the melee she was in stitches.

“It was so wonderfully funny,” she related, “It was like something out of Buster Keaton, those old black and white movies. Who else gets fruit thrown at them? I loved every moment.” Her sense of humour was, perhaps, one of the most misunderstood aspects of her music; a case in point, her 1977 track ‘Spangled Banner Minor and Other Patriotic Songs’ from The Carla Bley Band album took aim at nationalism. Po-faced critics called it “subversive,” “provocative,” or “avant garde.” It was hilarious.

She was born in 1938 in Oakland, California, to first generation Swedish immigrants. Her father was deeply involved with the church as choirmaster and organist, and Bley was brought up, as she said, “doused in religion.” But at least she was taught piano and was the only person in her father’s choir able to sing harmony parts in the ‘Messiah.’ When she had her fill of religion, “I was going through life scared of going to hell,” she left the church with a view to becoming a competitive roller skater, dropping out of school at 15 before running away to New York at 17. She got a job as a cigarette girl in Birdland, where she famously met her husband to be, pianist Paul Bley. He encouraged her to start writing music, her first composition was ‘Donkey,’ pretty soon followed by ‘Ida Lupino,’ recorded by Paul Bley, Jimmy Giuffre and others.

For a long while she didn’t set much store by her early work, dating her real achievements to the time she met (and later married) trumpeter Michael Mantler. Together they become leading lights in the Jazz Composers Guild, an orchestra that included, from time to time, Paul Bley, Cecil Taylor, Bill Dixon, Archie Sheep and Sun Ra and others. Her more ambitious period was marked by ‘Roast’ for the JCG, followed by ‘A Genuine Tong Funeral’ for the JCG but not performed by them. After the JCG collapsed, the orchestra continued as Jazz Composers Orchestra Association.

Meanwhile vibist Gary Burton had emerged as a leading figure in combining jazz and rock, and had begun using Bley’s compositions, such as ‘Sing Me Softly of the Blues,’ and ‘Fanfare/Mother of a Dead Man’. In 1967 he recorded Bley’s first full-scale project involving a 10-piece ensemble, A Genuine Tong Funeral (A Dark Opera Without Words). Her next major project was for Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra, where she wrote two tunes and arranged the rest. The concepts and ideas in Tong Funeral and Liberation Music found the apotheosis in Escalator Over the Hill, a musical encyclopedia for the eclectic and a pan-music pantechnicon all rolled into one. Released in 1972, it defined Bley.

But even after huge achievement of Escalator, her eyes were looking towards fresh horizons — rock, “I started hearing the possibilities of not borrowing from black culture,” she told Sy Johnson in 1978. “Actually finding substance in white culture. The Beatles best stuff was taken from Anglo-Saxon roots, I was amazed because I thought only black music was important.” So after Escalator’s little sister, Tropic Appetites, on Dinner Music she used the funk trio Stuff. In 1982 came Live! with a big band, where she confronts her religious upbringing on ‘The Lord Is Listening To Ya, Hallelujah!’ where her mischievous humour is not far from the surface. In 1975, still on the rock kick, she wrote the songs for Nick Mason’s Fictitious Sports, although when asked about that in interview she said, “We don’t talk about that.”

In the 1980s, she re-engaged with Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra. The record label she and her then husband Mantler owned to release their musical projects was called Watt music, which had a tie-up with ECM records. Manfred Eicher suggested she might record for ECM, rather than Watt, so she could concentrate on being an artist, which in an interview she suggested came as something of a relief. With her partner, bassist Steve Swallow and saxophonist Andy Sheppard, she toured and made four trio albums for ECM, miniatures that refined her art to its very essence, with her final album, Life Goes On, released in 2020.