Why listening on vinyl might make you think of jazz in a different better way

Sunday, February 5, 2012

When CDs were new the music industry predicted for years that the end was nigh for vinyl.

As the CD became the predominant format the gloomy prognosis seemed to be bang on the money and vinyl sales dropped and dropped. But as digital media now holds sway and CD sales are on the slide, the last year has seen a big uplift in vinyl. An endorsement surely for the view that what goes around comes around. Annual sales of vinyl had by October according to Official Chart Company figures, reached a six-year high in the UK, passing 240,000 units. While genuinely rare vinyl attracts often staggeringly high prices on a par with a particularly fine vintage wine or a highly sought after piece of rock and roll memorabilia, relatively recent releases, particularly 1970s and 80s pressings of hard to find albums can still be snapped up for £10 or less, less than paying for complete albums made in the CD era if you prefer to buy them track-by-track on iTunes. And of course there’s the added bonus of artwork coming with the vinyl, and album information that digital formats are less equipped to handle unless you like tiny thumb nails run off from a home printer.

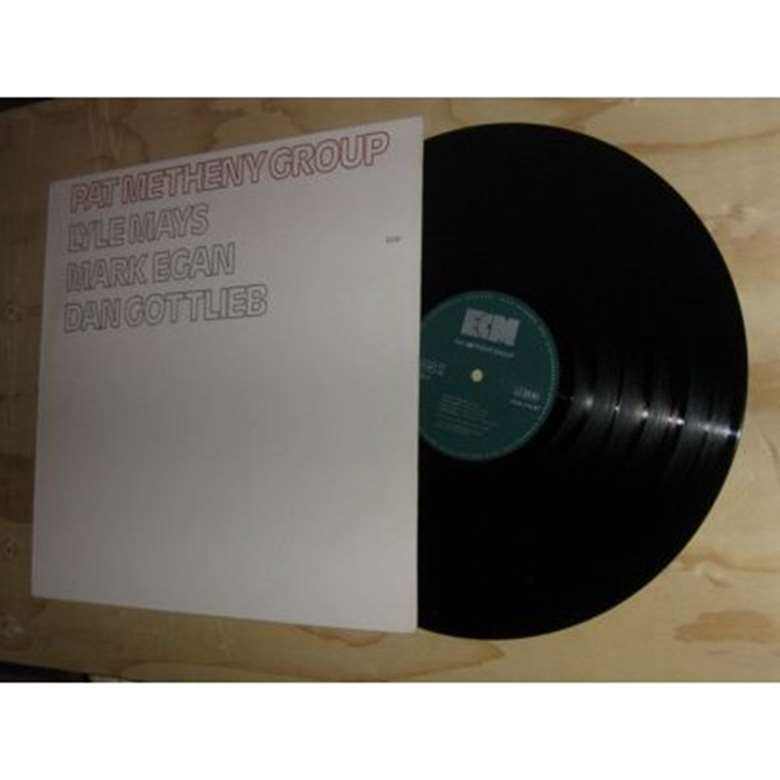

Take a recent sample purchase of the landmark 1978 album Pat Metheny Group, picked up on vinyl just last week for £8 in a small local second hand record shop specialising in jazz, reggae and soul vinyl. The pressing dates back to when the album was first released in the late-1970s. The whole process of its purchase is, as well as everything else, also very different to buying CDs or digital versions. First of all there’s the size to handle, then there’s the scrutinising (checking if the vinyl is scratched or not), looking at the dead wax for clues to pressing info, and all importantly reading the artwork. If you’re over the age of 30 of course you’ll know all this. But anyone younger consumes music without all this ritual. It’s flipping through racks rather than scrolling on a screen. There’s the smell of the sleeves, the sight of the artwork, the enthusiasm of the shop owner, the buzz of the deck and snap and pop of the needle on the vinyl when the disc is tried out and the intervention of the speaker livening up the deadness of the room.

With Pat Metheny Group, red-ish letters with hollowed out white middles for the three small words, 'Pat' 'Metheny' 'Group', and grey coloured outlines with white again for Lyle Mays, Mark Egan and Dan Gottlieb on an expanse of wallpaper white and the title letters ECM in grey block capitals are the first things you see. That’s all there is on the cover of Pat Metheny Group, an impact a tiny CD sleeve doesn’t make sense of and of course a visual aspect a computer file does without entirely.

The spine adds little more except the addition of the catalogue number, 1114. On the vinyl disc’s green label of the original pressing there’s a less familar chunky version of the Munich record company's logo. As it’s more down home than the current and longstanding version of the logo it’s as if someone has come to work dressed in their pyjamas.

While the cover of the album says little, flip to the back and a large landscape-sized photograph by Roberto Masotti, whose work has adorned many ECM sleeves over the years, with Metheny pictured in the middle with his back to a brick building with a closed door to his left and a window to his right. In front of the window in a sheepskin jacket buttoned up is Dan Gottlieb neatly captioned as are Lyle Mays to Metheny's left looking moody with his begloved left hand folded over his hidden right. With shoulder length hair like all the band Mark Egan with a hint of a moustace is positioned the most forward in the shot looking directly at the camera as they all do. Metheny was not a natural for ECM and despite his auspicious debut Bright Size Life and this album which lent its name to one of the most successful jazz rock groups of the last 40 years, when Metheny left for Geffen the move really began to establish him before maturing during the Warner years.

Recorded in January 1978 in Oslo engineered by the famed Jan Erik Kongshaug at Talent Studio, Side 1 is dominated by ‘Phase Dance’ which feels very West Coast and like something Bob James might have liked to have written. Opener ‘San Lorenzo’ is more sprawling at over 10 minutes long and less arresting in its theme. Side II's nod to Metheny's former bassist Jaco Pastorius on ‘Jaco’ is jazzier with solos and Mark Egan gives the tune a louche night club feel while Mays is relaxed and plays as if he’s in a club he likes. Dan Gottlieb sounds a bit like Steve Gadd on Steely Dan's ‘Aja’. It’s more of an active listen: you have to change the disc, clean it before putting in on and place it back in the sleeve carefully so the disc doesn’t fall out when it’s parked on your shelf. Oh, and it’s more tangible. Storing thousands of computer files in the Cloud is great but you can’t hold them and someday you might even forget your password or the technology moves on to make that storage solution a thing of the past.

Vinyl isn’t perfect, in fact its very imperfections, the scratches and basic fragility of the format, means that vinyl has a human element, that could well have kept it going all along. It doesn’t pretend to be perfect unlike the deceiving digital formats which as Greg Milner in Perfecting Sound Forever: The Story of Recorded Music examined plays disturbing tricks with the memory. What Milner maintains is that digital sound is not retained by the “musical memory” in the same way as analogue sound is. In a nutshell the music won’t stay with you. It lacks presence. Yet despite everything in its favour vinyl is only a format, and it’s foolish to think a format is more important than the music itself. However, as a conduit to getting close to the live performance you’d experience at a gig as well as adding in the tactile factors vinyl is so adept at introducing then a voyage of discovery, a vinyl attraction is surely a rite of passage. Who knows, jazz for you might never be the same again. Stephen Graham