How the vinyl revival continues to confound expectations

Stuart Nicholson

Thursday, July 18, 2019

Stuart Nicholson takes a look at how the 13-year-old vinyl revival has given rise to a new trend in analogue-focused nightlife and weighs up the pros and cons of the format against its digital opposition

Five months ago the Bar Shiru opened in uptown Oakland, California. Hardly an event calculated to set the pulses racing 5,000 miles away in the UK, but this was a bar aimed at the growing audience for analogue sound – behind the bar are about 1,000 vinyl records lined-up on shelves 15 feet high. Most of them are jazz: Miles Davis through to Kamasi Washington. Either side are two 812 Line Magnetic speakers. Also behind the bar are two expensive turntables alongside two LM-805IA amplifiers. This old-school, high-tech equipment fills the room with analogue sound of astonishing clarity. People come from miles around to sit, listen and enjoy a drink. Welcome to the latest twist in the current vinyl boom, a trend that’s being repeated in high-end bars and cafes from In Sheep’s Clothing in Los Angeles, to Public Records that opened in April in Brooklyn’s Gowanus neighbourhood, Brilliant Corners in Dalston and Classic Album Sundays, which started in 2013, to King’s Cross Spiritland that also opened beneath London’s Royal Festival Hall last December. Music – specifically, music played on a superior analogue sound system – has become a customer draw in its own right. The inspiration behind this new trend comes from Japan, and the growing popularity of kissaten, cafes and bars geared toward audiophiles, such as the Bar Martha in Tokyo’s Ebisu district and London’s own Gearbox Records listening sessions.

The vinyl boom has continued to surprise music business insiders, whose current model is increasingly based on a singles based sound-file culture and music streaming. Originally driven by a buoyant secondhand market for vinyl albums, a ‘new’ vinyl sector entered the market around 2006. Initially, sales were tentative, reaching one million in the US by 2007, yet by 2013 they had grown to 6.1 million – an increase of 600 per cent in just six years. This kind of exponential growth has continued to defy the music experts and, despite industry predictions that the year-on-year growth would plateau or even begin to fall back, Nielsen’s end of year figures for the US in 2018 hit another high, peaking at 16.8 million (up 14.6 per cent from the previous year). Based on the rate of growth from 2016 to 2018, Nielsen predicted vinyl sales in the US could soar to well over 18 million, with 20 million records sold not an unrealistic goal. Growth in the UK in 2018 was even higher, with vinyl accounting for sales of 4.2 million, a rise of 26.8 per cent over the 12-month period and 1,892 per cent up on the figure 10 years ago, according to the BPI. Demand for vinyl has even prompted leading digital distribution platform Bandcamp to develop plans to start pressing vinyl later this year.

Many critics claimed vintage vinyl sounded better, a debate that rages to this day

Initially, arguments raged over the relative merits of vinyl and compact discs. Despite claims the CD represented a significant advance in sound quality over the vinyl it replaced, early CD releases failed to achieve this, a characteristic blamed on early generation analogue-to-digital converters using ‘Brickwall’ filters that caused phase distortion, producing unnaturally harsh high frequencies, which is why audio magazines were so critical of digital recording in the early days. Once these teething problems had been sorted, a standard Red Book 16-bit resolution 44.1kHz CD covered the entire range of audible sound. Simply put, the more ‘bits’ you use, the more natural the music sounds and the faster the sampling rate, the wider the frequency range. Since the audible frequency range is typically from 20 to 20,000 kHz, using a higher sampling rate than that of a 16-bit 44.1kHz CD is mathematically inconsequential as the human ear will be unable to detect it. A CD also has a 26dB advantage over vinyl in terms of its dynamic range and no measurable wow or flutter. Nevertheless, many critics claimed vintage vinyl sounded better, a debate that rages to this day.

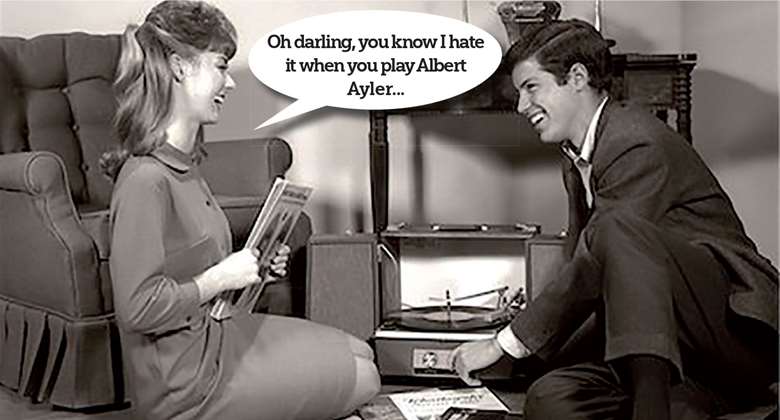

But the respective merits of sound quality somehow miss the point. Ownership of vinyl presupposes a different relationship with music to digital since it implies active engagement. Albums were intended to be listened to from beginning to end, with just one flip in the middle. The duration of an LP – approximately 20 minutes a side – may have been determined by the limitation of available technology, but seems perfectly judged. Files on CDs and MP3 might end in silence, but the regular click when the pickup head reaches the central groove when one side of an LP has played through is a nagging call to action: get up, turn over, or choose something else. The album as a track-by-track experience central to listening experiences of classic LPs such as A Love Supreme, Dark Side of the Moon and Sgt Pepper has returned.

Another key aspect of the 12-inch LP was a return of the iconic status of cover art and the subtle signals it projected – for example, Mati Klarwein’s visionary Afro-centric artwork for Miles’ Bitches Brew. As more and more vinyl reissues of past classics came onto the market, vinyl converts began discovering certain albums could withstand repeated listening and, as their relationship with the music deepened, not only did the music seem to get better, but it also began to assume greater meaning. But as vinyl collections began to grow, something seemed out of kilter. The past increasingly seemed more inviting than the present. Classic albums seemed to possess greater depth and gravitas than current releases, causing some to wonder if the greatest danger to the future growth of music was… its past.