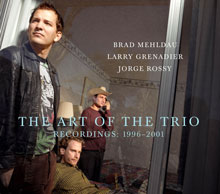

Jazz breaking news: The Art Of The Trio Years Are Recalled On Just Released Brad Mehldau Box Set

Tuesday, December 13, 2011

The mid-1990s and early-2000s seem a long time ago now.

Babes in arms back then mewling and puking, not yet ready to pick up their first instruments, were oblivious to most things beyond their mother’s milk. But for five years from 1996 the Brad Mehldau Trio were playing music together that few at the time could ignore and which with The Art Of The Trio – Recordings 1996-2001 still more will arrive at.

Released just yesterday we can get a glimpse for the first time in the greatest depth possible so far exactly what pianist Brad Mehldau, double bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Jorge Rossy were laying down in the studio and playing live at New York jazz club The Village Vanguard. It's all documented in one place in a carefully annotated box set with additional unreleased material.

It’s all a time that now seems as distant as the Stone Age, when the World Wide Web was only five years old. Flash forward to 2011, what the three individuals of the trio have been doing this year is an instructive contrast. Mehldau has recently completed his Wigmore Hall residency in London in the company of Don’t Give Up On Me producer, the singer/songwriter Joe Henry. Grenadier has been touring with the great Pat Metheny. And Jorge Rossy, after relocating to Catalonia, has been performing during 2011 with the formidable Seamus Blake on the festival circuit playing electrobop.

The Nonesuch box set collects the five original Art of the Trio albums spread over six discs with the seventh CD featuring previously unreleased material from the Village Vanguard in New York recorded there in three separate bursts spread over six years. Brad likes his New York clubs and occasionally pops up unannounced at places like the Village club Smalls.

Mehldau despite his fame nowadays is still strictly counterculture in spirit, an enigma, which is very much part of his appeal. The very first track, ‘Blame It On My Youth’ of The Art of the Trio Vol 1 is very slow and vinegary, as unglossy as it comes. If you listen to it while looking at a fairly unrecognisable picture of him in the artwork staring half apologetically it's a picture that makes you think of the work and creative vision of W. Eugene Smith. On the opposite page the arrow is a good deal less subtle and the word “Entrance” is there with a big drop shadow. OK, he’s new.

When Mehldau first appeared on the scene people were quick to say “the new Bill Evans” a description that was meant as a compliment but which quickly became a cliché and clearly baffled both Brad and fans. He interprets more rhapsodically on ‘Blame It On My Youth’ and he isn’t really so nearly modal mainly because his left hand is so different. Hindsight is a great thing – but listen if you get a chance to ‘Blackbird’, the fourth track on Art Of The Trio Vol 1.

These days Brad has a parallel reputation for interpreting alt. rock and post grunge. He’s pretty good on doing Lennon/McCartney too. ‘Dear Prudence’ is the one Mehldau has made his own and sometimes when he’s improvising his original tunes he affectionately defaults to ‘Dear Prudence’-flavoured cadences. ‘Blackbird’ is wonderfully non twee here, something that is good in itself but because the interpretation is also optimistic rather than say arch, Mehldau manages to bridge the gap and also improvise a great deal.

The box set has notes by the professorial Ethan Iverson whose blog Do The Math has become as required reading as the often chaotic progress of his post-kitsch trio The Bad Plus is necessary listening. “Brad loves”, Iverson says, “German romantic poetry, and the chords of the originals ‘Ron’s Place', ‘Lament For Linus’, ‘Mignon’s Song’, and ‘Lucid’ somehow sound like 60s innovations of Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock filtered through the sensibility of Rilke and Goethe.”

Matt Pierson who produced all these records goes way back with the pianist and midwifed the startling Introducing Brad Mehldau a few years before the first of the recordings here. If you’ve heard Mehldau’s most recent album Live In Marciac released this year you’ll know without even hearing a note here that he plays live as if he were in a studio and sometimes in the studio as if it were a live show but manages in both contexts to channel the adrenalin and naturalness needed whether by a process of zen, or supreme concentration, which keeps him free to experiment within his carefully constructed idioms.

Volume 2 is a live album unlike the first one and as happens sometimes in famous big city jazz clubs like the Vanguard performers are cast back to a lost time, a place that probably never existed although the memories of the memories are everywhere. Listen to ‘The Way You Look Tonight’ and you’ll see what I mean – it’s kind of cheesy for a minute and then suddenly a lightbulb explodes and Brad manages to avoid hurtling down a nostalgic lift shaft. It’s very expansive and an indication of his increased confidence by this stage just to be himself.

Songs, Volume 3, is crucial in that process of Mehldau being himself. His interpretation of an at-that-time little known Radiohead song ‘Exit Music (For A Film)’ is after the seed of ‘Blackbird’ the beginning of a new phase. Since then although it’s now beginning to fade a bit Mehldau has become synonymous with his credible versions of Radiohead songs, a process that reached its creative peak after this trio disbanded, on Day Is Done – and his version of ‘Knives Out’.

The other noteworthy aspect of ‘Songs’ is the version of Nick Drake’s 'River Man'. Drake, who of course checked out too soon, Brad can get inside just as he can another early departer Elliott Smith. To pick up on what Iverson is saying, it’s the doomed hero Mehldau is drawn to time and again: the one who makes you think, who delivers that imperfect song with the perfect instincts and the half realized meanings.

Larry Grenadier on ‘River Man’ throbs like a latterday Charlie Haden and like Gary Peacock is to Jarrett, Grenadier is to Mehldau, hiding there in plain sight, playing like you could only dream about. But Rossy is the real mystery man of the box set. When Jeff Ballard eventually came in to take his place and move the trio into another direction as Brad himself was changing it was easy to forget Rossy but hearing him here makes you think again and realise that he was a difficult drummer to follow. Like say Seb de Krom Rossy weighs every note and has superb time, what every drummer needs and many spend their whole lives without.

When Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein’s ‘All The Things You Are’ plays in a jazz club I always know it's the right place to be. Back at the Vanguard, the fourth volume begins with this tune on an album that picks up the pieces and feels authentic enough but is a bit rough and ready. Brad doesn’t feel at home in the first two minutes of the song it’s pretty clear but conversely that’s why his interpretation works. It feels as if he’s stumbling around in the dark but enjoying the lostness. The fifth volume Progression is notable for ‘Resignation’, one of Mehldau’s most substantial compositions, and an intriguing version of ‘Cry Me A River’. Forget the bombast, and the people lying around prostrate on the floor cold calling their emotions in when they do this song. Rossy on brushes is also ideal.

'London Blues' opens the final disc. It feels like a jam and even today there are songs when Mehldau plays live that you somehow know must make him feel good despite everything but really are pretty throw away. ‘London Blues’ is like that, and the version here of ‘Unrequited’ is maybe not the deepest. However, ‘In The Wee Small Hours Of The Morning’ is worth playing time and again. You don’t have to be a Brad fan or were a baby in the 1990s to buy this box. It probably helps though if you’re still a Brad doubter. If you are, draw the curtains, listen to this remarkable trio. You might even think about jazz anew.

– Stephen Graham