Life-changing jazz albums: 'Spiritual Unity' by the Albert Ayler Trio

Monday, July 22, 2019

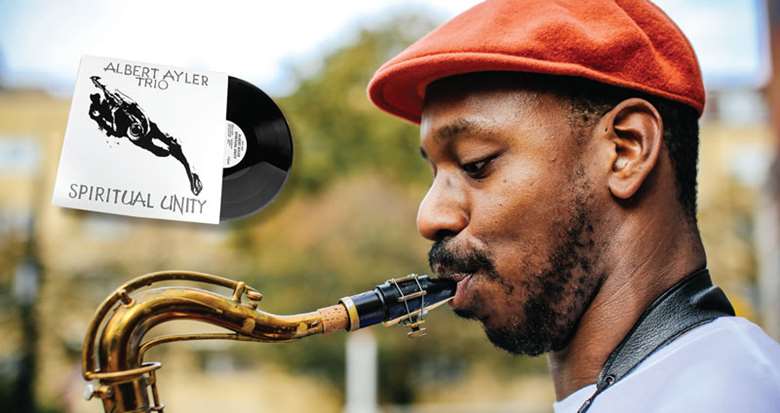

Saxophonist Shabaka Hutchings talks about the album that changed his life, Spiritual Unity, by the Albert Ayler Trio.

Interview by Brian Glasser

It was really easy for me to decide: Albert Ayler’s Spiritual Unity. I got the copy I own at Ray’s Jazz shop, but I heard it first at Guildhall – I went to the Barbican library and took out the CD. I saw the cover and liked it – a man merging into a saxophone. Although I’d heard of Ayler before then, I hadn’t checked him out.

So I sat down and listened to it – and I didn’t understand anything! But it was kind of interesting. This would have been in 2005 – I was about 19 or 20. At that time, I was listening to ‘normal’ jazz – Hank Mobley, Wayne Shorter, standard stuff. Modern-wise, everyone was into Mark Turner, Joe Lovano, Chris Cheek. Then all of a sudden there’s this guy just blowing the saxophone really hard. And it wasn’t about the harmony, or the specific notes, it was just sort of a texture. My brain couldn’t compute it. Before, I’d been listening for what I could take from something – what I could transcribe and use for my own solos. But this was untranscribable – it seemed like there was nothing to steal from it. It sounded like he was crying through the saxophone. You can hear vocalisation in Sidney Bechet and the older guys, but this was the first time I’d heard someone follow through on that and not try to mesh it with something more conventional.

Even at the start, there was something I liked in it. I can’t really put into words what it was; but something made me not want to turn it off. It might be that I liked the melodies, though there weren’t many of them. A piece might start off bluesy, then he’d just go off. And I really liked Sunny Murray’s drumming. I’d not heard any drumming like that – he was moving with the saxophonist, but in terms of intensity rather than rhythm. I could also hear the interaction was very deep – they’re all listening to each other, they’re not trying to follow each other in an orthodox way. I liked to concentrate on Gary Peacock and imagine I was him – soloing, but listening to everyone else.

‘Whatever Ayler does, it’s about the emotional intent behind it’

Back then I thought, ‘I’m just going to have to learn to listen to this music – in fascination and enjoyment’. The more I listened, the more I realised that it’s in what Anthony Braxton calls ‘an emotional zone’ – whatever Ayler does, it’s about the emotional intent behind it. I wanted to see whether I could get into that space where you’re free to do that. It’s all about the big picture – more like painting.

It made me listen more carefully to the other – ‘normal’ – stuff too. It’s easy to just learn the harmonics matrix and subconsciously you’re not listening properly any more. Everyone always says, ‘Listen [to your fellow musicians]’, but in the course of learning jazz – especially then, I think – you get preoccupied with trying to solve the equation. It’s very seldom you actually really listen. As a sax player, you play your stuff, try to make a good sound, try to get all the substitutions and the chord changes right – but you don’t let all that go and respond to what you’re hearing. Charlie Parker said, ‘You practice and practice; and when you get on stage, you forget it all’.

A couple of times in jam sessions, say playing ‘Giant Steps’ – at a reasonable tempo! – I tried to just listen to the bass-line and stay on every note he played and play things that sounded good on that, just as an experiment. And it worked! So from then, I tried to play stuff that I thought actually worked over what was happening, as opposed to listening and then playing stuff that I knew would work because it was ‘correct’. The conventional approach can get your mind in a tight place, where you have to prove what you’ve learned, otherwise you haven’t worked hard enough or whatever – even though you might not be fully committed to what’s happening. This other approach is all about integrity of intent. It makes everything simpler in a way, although it’s really hard! I only think I’m getting close to achieving it now.

With the classical music I was studying, I enjoyed the challenge of learning a piece and playing it without any mistakes. I like that split, that there was nothing connecting it to my jazz playing. Maybe by doing that training it made me not worry about playing free – because I knew I could play what people would term ‘properly’.

The album

Albert Ayler Trio

Albert Ayler Trio

Spiritual Unity

ESP-Disk' (1964)

Albert Ayler (ts), Gary Peacock (b) and Sunny Murray (perc).

Tracks: ‘Ghosts: First Variation’, ‘The Wizard’, ‘Spirits’, ‘Ghosts: Second Variation’.

This article originally appeared in the November 2016 issue of Jazzwise. To find out more about subscribing, please visit: www.jazzwisemagazine.com/subscribe