Branford Marsalis – Spiritual Soliloquy

Thursday, October 8, 2015

Branford Marsalis has always tackled every musical challenge head on – be it playing arenas with Sting, freewheeling improvised rock with the Grateful Dead, primetime US television shows or leading one of the hottest quartets in contemporary jazz.

Yet, as he tells Stuart Nicholson, the idea of playing a solo saxophone concert in San Francisco’s hallowed Grace Cathedral, was one that left even a saxophonist as gifted as him doubting his abilities

Given the astonishing breadth of Branford Marsalis’ career, not just in jazz but as a soloist with both symphony orchestras and chamber groups in the classical world and a session-enhancing guest on an array of pop and rock sessions, there has been one box in the 54-year old saxophonist’s curriculum vitae that has steadfastly remained unticked – the solo concert and recording. It’s an undertaking not to be taken lightly, since by Marsalis’ own admission, just 10 years ago he felt unready for the challenge. But then destiny intervened. “Like much of the things in my career that solo concert has that random feel to it,” says Marsalis, adding, “I do, however, believe in some sort of cosmic thing, force, that provides you with opportunities, not with success.” Thus when SFJAZZ contacted him in 2012 about a solo concert, he felt that maybe the time was right. A date and venue were set, 5 October 2012, at Grace Cathedral, San Francisco, famously the site of Duke Ellington’s Sacred Concerts in the 1960s.

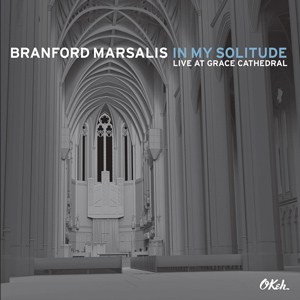

Having agreed to the concert, Marsalis was characteristically philosophical: “When I knew I was going to do the concert, my manager let my engineer Rob record it – if it’s good we release it, if it’s shite, well, I have this big pile of shite that I can listen to – to remind myself how much better I need to be.” During his preparation Marsalis was well aware that the solo concert presents as much a challenge for the musician as it does for the audience, something he confronted head-on. “I started re-listening to solo saxophone records, and what is the thing I don’t like about them? The thing I didn’t like about them was the monotony. I have a good friend who is an actor, Roger Smith, and he basically does movies and all the other lines so he can subsidise his one-man plays, and they are incredibly difficult because you can’t simply walk into an environment with only your point of view because people will be completely bored listening to you for an hour and a half – it’s perfectly fine for 10 minutes but you have to find a way to be other people and different styles of music constitute greatly to that – that ability to become a different person or a different character within the sphere of instrumental music. So then I started putting together a list of things, like classical things that are well written in a solo context, and songs that have great melodies, because if you’re playing great melodies people don’t mind the rest of it. If an audience has to have a music degree to understand what your purpose is then it is not going to be a success. It is our job to learn all this music and distill this information down to a pithy narrative that audiences can understand.” In the event, the concert and the album of the event, In My Solitude: Live at Grace Cathedral, his latest release and debut on the OKeh label, was both an artistic and aesthetic success, providing further evidence, if evidence is needed, of Marsalis’ continuing artistic growth and evolution as an artist.

Having agreed to the concert, Marsalis was characteristically philosophical: “When I knew I was going to do the concert, my manager let my engineer Rob record it – if it’s good we release it, if it’s shite, well, I have this big pile of shite that I can listen to – to remind myself how much better I need to be.” During his preparation Marsalis was well aware that the solo concert presents as much a challenge for the musician as it does for the audience, something he confronted head-on. “I started re-listening to solo saxophone records, and what is the thing I don’t like about them? The thing I didn’t like about them was the monotony. I have a good friend who is an actor, Roger Smith, and he basically does movies and all the other lines so he can subsidise his one-man plays, and they are incredibly difficult because you can’t simply walk into an environment with only your point of view because people will be completely bored listening to you for an hour and a half – it’s perfectly fine for 10 minutes but you have to find a way to be other people and different styles of music constitute greatly to that – that ability to become a different person or a different character within the sphere of instrumental music. So then I started putting together a list of things, like classical things that are well written in a solo context, and songs that have great melodies, because if you’re playing great melodies people don’t mind the rest of it. If an audience has to have a music degree to understand what your purpose is then it is not going to be a success. It is our job to learn all this music and distill this information down to a pithy narrative that audiences can understand.” In the event, the concert and the album of the event, In My Solitude: Live at Grace Cathedral, his latest release and debut on the OKeh label, was both an artistic and aesthetic success, providing further evidence, if evidence is needed, of Marsalis’ continuing artistic growth and evolution as an artist.

Selecting a wide range of material and interpolating it with his own spontaneously conceived melodic extemporisations he forms a creative continuum within the overall arc of the performance – for example, Steve Lacy’s ‘Who Needs It’, gives way to Hoagy Carmichael’s classic ‘Stardust’ which gives way to the first spontaneously conceived interlude, which then leads into ‘Sonata in A minor for Oboe Wq. 132’ by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, performed on tenor saxophone, and so on. This creates a tension between melody (resolution) and improvisation (postponed resolution) and heightens audience anticipation as one section leads into the next creating a certain creative frisson whether audience expectation will be postponed or resolved. What emerges is a pretty complete performance as the narrative is driven forward by tension and release, with the improvised sections key to the album’s success. “I didn’t walk in there with the expectation we might have anything, I thought we might get half a record, and we could use it later, I didn’t think it would be one of those situations that when I would listen to it I’d say, ‘Wow, this whole thing is pretty good!’ So, I was pleasantly surprised.”

Selecting a wide range of material and interpolating it with his own spontaneously conceived melodic extemporisations he forms a creative continuum within the overall arc of the performance – for example, Steve Lacy’s ‘Who Needs It’, gives way to Hoagy Carmichael’s classic ‘Stardust’ which gives way to the first spontaneously conceived interlude, which then leads into ‘Sonata in A minor for Oboe Wq. 132’ by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, performed on tenor saxophone, and so on. This creates a tension between melody (resolution) and improvisation (postponed resolution) and heightens audience anticipation as one section leads into the next creating a certain creative frisson whether audience expectation will be postponed or resolved. What emerges is a pretty complete performance as the narrative is driven forward by tension and release, with the improvised sections key to the album’s success. “I didn’t walk in there with the expectation we might have anything, I thought we might get half a record, and we could use it later, I didn’t think it would be one of those situations that when I would listen to it I’d say, ‘Wow, this whole thing is pretty good!’ So, I was pleasantly surprised.”

Coincidental to the release of In My Solitude is a three-album package Wake Up to Find Out by the Grateful Dead, a live concert recorded on 29 March 1990 with none other than Branford Marsalis as a guest. On it Marsalis frequently builds up a head of steam in context with the Dead’s unique brand of rock, so what does the saxophonist remember of that occasion?

“I remember a lot about it because the Grateful Dead, I mean they were really ahead of the curve with a certain understanding, a business model that was essentially theirs for a long time, they basically developed their own clientele, and this is pre-internet, so they had all these people who would sell-out stadiums, sell-out arenas and it was completely under the radar! Completely under the radar. I said, ‘Oh, the Grateful Dead, I’m going to play with them and have some fun.’ I didn’t expect it to be sold-out, 18,000 people, because you didn’t hear about it, it wasn’t in the media, it wasn’t on television, it wasn’t on the radio, and the place is fucking packed! Holy shit! So that part of it was super cool to watch, it really brought home to me the importance of trying to develop your own clientele. And the other side of it was you could just hear the musical influences of each person while you were doing it, like Bob Weir was a rocker, [Jerry] Garcia was like the blues and folk guy, Phil Lesh was the jazz guy, [Bill] Kreutzmann was the jazz guy, Mickey Hart was the world music guy, and at that time the piano player was Brent Mydland – I didn’t really get a feel for him, he died not long after the concert. But the thing that was really amazing to me was at that time they were on stage calling tunes, which I think is so beautiful and wonderful, like in the era of set-lists, they were basically calling tunes and it was impressive how wide their range was, because they played other people’s tunes without hesitation. A lot of bands today they just know their music and nothing else, and that regrettably includes jazzers as well, it was just a great experience, and contrary to popular myth, it’s easy for me to play that style of music with conviction, I was right on the heels of the Sting tour and I was good at it, it was a great night, it was fun!”

Mention of Marsalis’ association with Sting dates back to 1985, when the singer formed a ‘super group’ along with Kenny Kirkland on piano, Daryl Jones on bass and Omar Hakim on drums, Downbeat noting that “though 1985 was a surprising, and in may ways exciting, year for music, possibly the most exciting – and certainly the most surprising – development took place with the collaboration of a British pop star with four young, conscientious, open-minded American jazz musicians”. And it was an exciting band, so what were Marsalis’ recollections of this collaboration? “Those are more intimate memories because I was actually in the band, and I didn’t want to be one of those R&B sax players that constantly play and they just turn him off and turn him back on when necessary, so I needed to watch his mouth, study what he did, know when I could play and I couldn’t play.”

Perhaps the best representation of the band is on the two LP set Bring on the Night, with an extended title track notable for Kenny Kirkland’s piano solo and a rap interlude by none other than Branford Marsalis. “It started out – this was back in the era of The Sugarhill Gang, it was just a novelty. I kind of blithely said on the tour bus, ‘Shit, anybody can do that, man!’ And Sting says, ‘Really?!’ So, on the stage in Dallas, unannounced, Sting says, ‘I was talking to Branford today and he said anybody can do rap, so Branford’s going to rap for you right now!’ The audience applauded and I said, ‘I’m not doing that shit!’ And he says, ‘Oh yes you are, we have all night!’ And he folds his arms, and stares at me for over a minute and I can’t believe this shit is happening! [laughs] So I basically had to like – I used that minute to compose some corny words, I just did it and unfortunately for me it became part of the schtick for that song for the rest of the tour. How humiliating! [laughs] I learned a lot on that tour and Sting’s a wonderful person and a really incredibly smart guy and helluva song writer, it was a great experience and I learned a lot – like the songs I wrote for Buckshot Lefonque were definitely influenced by Sting’s music.”

Buckshot LeFonque, Branford Marsalis’ alter ego that combined jazz with rock, pop, R&B and hip hop, recorded two albums between 1994-97. And while it caused quite a stir in jazz at the time it was just one more facet of Marsalis’ range that extends from a three year stint as Jay Leno’s bandleader on the famous Tonight Show on American television, as a composer for film on the soundtrack of Spike Lee’s film Mo’ Better Blues and as a composer for theatre with August Wilson’s Broadway production Fences that earned a Tony Award nomination. His last quartet album Four MFs Playin’ Tunes, was named Best Instrumental Jazz Album in 2012 by iTunes while this interview was conducted midway through a tour as guest soloist with leading American symphony orchestras. If there is one guiding light to this remarkable career it must surely be in the famous quote by Duke Ellington that there are only two kinds of music – “good music and the other kind,” the former celebrated throughout the 11 numbers that comprise In My Solitude: Live at Grace Cathedral.

Discover...

Feature John Coltrane – Giant Steps

Feature Wayne Shorter – Music of the Spheres

Feature Sonny Rollins – Tenor of Our Times

This article originally appeared in the Dec 14 / Jan 15 issue of Jazzwise. Subscribe to Jazzwise

Photos: 1) by Palma Kolansky; 2) by Tim Dickeson