James Brandon Lewis interview: “I know how to be me in all contexts”

Kevin Le Gendre

Thursday, June 13, 2024

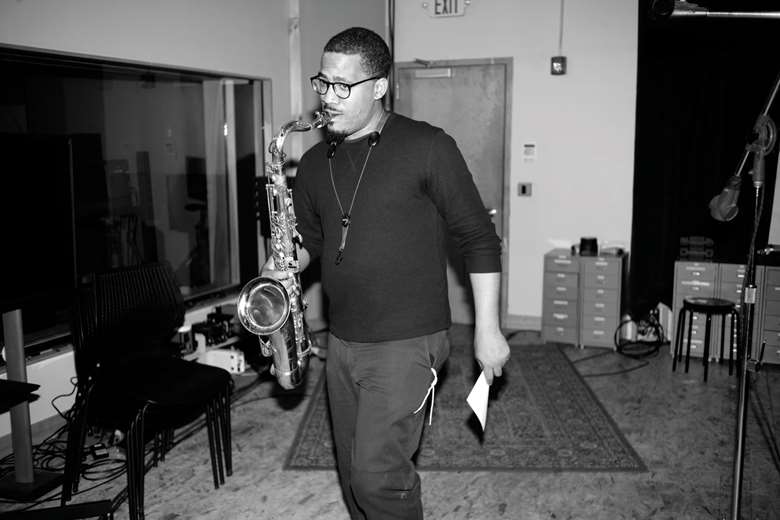

One of the most exciting player-improvisors of his generation, James Brandon Lewis skilfully negotiates the divide between the populist mainstream and the avant-garde. Kevin Le Gendre meets him ahead of his headline appearance at this month’s Love Supreme Jazz Festival

Call it the rigours of the road. Many hazards can trip up an artist on tour, from the woe of homesickness to the blight of fatigue and the curse of illness. Above all, time, a very precious entity for improvising musicians, is hard to control. James Brandon Lewis proves as much, arriving late for our interview at London’s Vortex club, where his quartet has a hotly-anticipated gig in just a few hours. He is up against the clock.

“For whatever reason, the plane didn’t land ‘til later than planned, then there’s going through customs, getting all the luggage, so by the time you get on the bandstand you’ve probably gone through more than a construction worker in a day,” he says, still looking fresh following a flight from Mantova, Italy. “And we’re in a different city every night. Being busy is good, but being away from my family is not so good. There are plenty of challenges, but by the time I get on the bandstand it’s all good.”

The number of dates racked up by the 40-year-old saxophonist has certainly been increasing over the past decade in direct proportion to his high quality output.

I have the sense to know that my playing comes from a lot of places. I’m not the ‘out-est’ of out and I’m not the ‘in-est of in’. I think I‘m just blurring the lines

While his Quartet recently released its fine fourth album Transfiguration, Lewis has been leading a quintet, Red Lily, which, like the aforesaid group, offers an inventive take on acoustic music. He is also heard to great effect in the electric ensemble, The Messthetics, a feisty collaboration with noted Washington DC punk band, Fugazi.

Furthermore, Lewis has just recorded with three leading jazz artists of different generations, trumpeter Dave Douglas, drummer Ches Smith and guitarist Ava Mendoza. More activity means more gigs.

“I used to tour in fall, winter, spring and a little summer,” he says, sipping a gin and tonic. “It’s been increasing this year because I am involved in various other projects. Where it used to be three times a year, it’s turned into four or five. But touring is part of the goal to get the music to people.”

For those who missed the sold-out show at the Vortex there will be an opportunity to see Lewis’ quartet in July at A Love Supreme, one of the premier British outdoor jazz festivals of the summer, known for its broad-church bill and stunning setting.

“I’ve always wanted to play there. Sure it’s different to some of the clubs I play,” he says. “But then I know how to be me in all contexts.”

Which is an interesting statement, as Lewis has emerged as an emblematic 2010s player whose skill as a composer-improviser is matched by his ability to make music that can be both accessible and abstract. That means that he is as effective in Heroes Are Gang Leaders – a group whose dense, multi-layered sound features the wily poetry of Thomas Sayers Ellis – as he is in his trio, comprising bassist Luke Stewart and drummer Warren Trae Crudup, who together make a tough but cultured noise that bridges funk, rock and the avant-garde.

Lewis made an impression with his commanding, granite hard tone and phrasing that has the bullish attack and fiery energy heard in many historic jazz reed players, but there were moments when he revealed ideas that stemmed excitingly from hip-hop, none more so than a thrilling backspin scratch effect. It pointed to serious study on his instrument and a desire to put a personal stamp on his work. If the 2016 trio was an impactful vehicle then the New York-based saxophonist upped the ante a few years later by forming a startling duo with noted Chicago drummer Chad Taylor that was documented on two CDs, 2018’s Radiant Imprints and 2020’s Live In Wilisau, further underlining Lewis’ gifts as a soloist and accompanist in a daringly exposed setting which saw him support, challenge and be challenged by his partner’s advanced rhythmic intricacies. Both musicians reached a very high level of communication.

As with his significant predecessors, from American icons such as David Murray to British legend Steve Williamson, whose flights of fancy he loosely recalls at times, Lewis is very much a contemporary player who has a number of vocabularies on which to draw.

“I have the sense to know that my playing comes from a lot of places,“ he says earnestly, gently adjusting the glasses that give him a scholarly air. “I’m not the ‘out-est’ of out and I’m not the ‘in-est of in’. I think I‘m just blurring the lines.”

The band that has become the most effective and consistent vehicle for this modus operandum is Lewis’ quartet, which stands as one of the most compelling acts in small group jazz, as was clear from the rapturous response it received at the London Vortex gig. Aforementioned drummer Taylor, double bassist Brad Jones, who hails from New York, and pianist Aruan Ortiz, a conspicuous addition to a long lineage of Cuban virtuosi, form the rhythm section that is anything but a backing band for Lewis. The saxophonist is fully aware of the founding fathers of the four-into-one, one-from-four ensemble, with Coltrane, Rollins, Shorter and Murray being primary exponents, and the great challenge of picking up the baton was one that Lewis willingly took up.

“Yes, it was very intentional,” he says, instantly. Lewis is clad in a black jersey and dark jeans, a discreet style that he wears well. “I think all my work is about having a conversation with the past. So I felt in 2019 going into 20 that I had a vision for this group, my quartet. I had played with each one of the members in various contexts, and, of course, I thought about the classic groups we all know. For me having a quartet was very intentional, as it was really an opportunity for people to hear me play with a piano, which hadn’t happened since 2010. So it felt like that was necessary.

“Even when I was writing for the trio, I still did it on the piano,” he continues. “It was a way to let the audience know what I’m thinking about without me saying it explicitly. (With the quartet) it’s there. I’m just thinking melody on top of melody on top of melody. Structurally, in the title track, for example, the lines are shifting and shifting a lot, as it’s an exploration of 12 tones that are changing over four bars.

“On some songs the melody just keeps opening up, going different places. And that’s what I do like about having a piano. I can get a lot of other colours than with the trio, although the trio music is still rich. There’s a connecting thread with all the ensembles because they all have weird twists. I guess what I do is more tricky than I thought, but also it’s not overly complicated. I don’t think of music in terms of complexity, I have a way of working, but melody is a lifeline. It constantly shows up, there’s something inside me that wants to emote, I just want you to feel every note I’m playing.”

Lewis has made an impact precisely because of his ability to create themes that are variously full of tenderness, passion and longing while using harmonic and rhythmic devices, above all the unrelenting push of lengthy sequences of notes, that keep his compositions moving in every way. In any case his artistic development has been quite fascinating. Born in Buffalo, New York state, Lewis attended the historic black university Howard and did research into gospel traditions, which is hardly surprising given that his father is a Baptist minister, before committing to improvised music.

That said, his origins in the church have regularly surfaced in his work, from his auspicious 2014 debut album Divine Travels to his tribute to gospel icon Mahalia Jackson, For Mahalia, With Love, which also stemmed from his desire to “recognise and celebrate a powerful black woman.”

But Lewis, who has a soft yet authoritative speaking voice, has had a longstanding interest in many pioneering figures as well as concepts, be they in arts and science or philosophy and politics, and he makes a notable statement about his formative years that says much about his inquisitive ways. “When I was 12 I got Joshua Redman’s first album,” he says calmly. “ He had a tune called ‘Groove X’ and I was like what does that mean? It kind of intrigued me, and I found that it was about Malcolm X. The title made me think. I like referencing.”

Systems are thus an important part of his creative ethos, which partly reflects the influence of one of his significant tutors, Wadada Leo Smith, with whom Lewis studied at CalArts, and who has created his own illustrated scores, known as Ankhrasmation. Lewis devised his Molecular approach to composition which is both metaphor and practical idea, whereby a theme can conceal many linking elements that may not be obvious on first hearing. There is a certain amount of cryptology at play.

“Basically, I was interested in the whole African-American quoting tradition, coded information, the idea of hiding things within melody lines, rhythms within rhythms. “We were hiding phrases under phrases,” he says. “I was listening to recordings of my improvisations and I could hear these things like a chain of communication. I enjoy books and I enjoy the process of creating a world that can be an environment for me. And it’s like a piece of artwork, it’s very personal. It’s away from the idea of music as utility… it’s music as something that I can imagine into being as part of its own world. It’s all metaphor and hidden meanings… one thing being inside another.”

While Lewis is clearly an individual with a strong artistic vision, he is keen to acknowledge the role that others, Smith being a case in point, have played in his development. As has often been seen since the genesis of jazz, a younger is significantly benefitting from the wisdom of elders. Here Lewis praises William Parker, Brad Jones and Chad Taylor, in their seventies, sixties and fifties, respectively.

“Having these gentlemen in my bands has affected me very specifically because of the range of their work,“ Lewis says with a smile. “They’ve both played with really amazing people; they’ve played with all of my heroes. So I also wanted to move into playing with people who are older than me, more senior than me because I felt like I needed that. I needed people that are around my age, but then also a bit older.

“I needed that experience, or for that residue of their experience to rub off on me,” he says, his voice becoming more emphatic. “And for them to challenge my own music. Just because I wrote it, that doesn’t mean that I can’t be challenged. They are such great musicians, so they can do that. With all the great bands you think of there’s a beautiful relationship happening where people are trying to figure things out, to work it out, encouraging each other to focus harder, which is just a key thing in the music.”

James Brandon Lewis Quartet appears at Love Supreme Jazz Festival, Glynde Place, Sussex on Friday 5 July

This article originally appeared in the July 2024 issue of Jazzwise magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today