Billy Cobham: The ‘lost’ 1980 interview

Jon Newey

Thursday, June 13, 2024

Back in March 1980, nine years after his unforgettable debut with the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Billy Cobham was still riding high. Jon Newey, then working for music weekly Sounds, managed to grab a rare interview with the drummer, which was published in the paper's 10 May edition. It's reprinted here (with a new introduction) for the first time in 44 years, and provides a fascinating snapshot of Cobham's career and ambitions at the time

Billy Cobham was at an interesting career juncture by Spring 1980. By far the most forward looking, technically advanced and influential jazz-rock fusion drummer of the time, with a top-drawer CV encompassing Horace Silver, Dreams, Miles Davis, Mahavishnu Orchestra, CTI label sessions and a string of inventive and successful solo albums for Atlantic and Columbia, he refused to be pushed in an overtly commercial direction – like a number of fusion players in the late 1970s – and was returning to the directions opened up the hard jazz-rock edge of his landmark album release, Spectrum.

He'd just arrived in the UK from his base in Switzerland for three sold-out drum clinics following a gruelling five days demonstrating the Tama brand drums he endorsed and explaining the developments in quality and construction, which pointed the way to today's high level of quality and durability, to packed meetings of international drum dealers at the Frankfurt Musik Messe, then the world's biggest instrument trade fair.

At this time Cobham was highly involved in pushing the capabilities and sonic range of the acoustic drum kit to its broadest limits. His formidable technique, time and mile-wide groove, from pinpoint articulation to multi-bass drum polyrhythmic turbo-drive, demanded high levels of fitness training, practice and study as opposed to the lure of the bar and bugle, favoured by more than a few drum greats over the years. He also had a deep interest in the development of drum synthesisers and electronic kits (then in their pre-digital infancy), and drum processing effects. Conversely, he also signalled a return to his acoustic jazz roots.

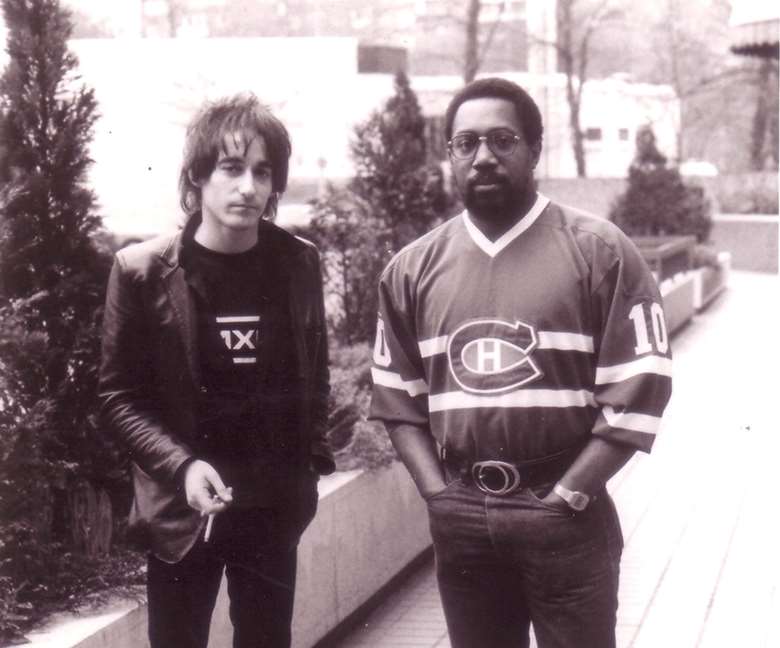

Never one to seek the limelight, Cobham gave few interviews back then, but having been introduced to him days earlier at Musik Messe by jazz guitarist Maurice Summerfield, I was able to grab time with him when he arrived at the Holiday Inn, Swiss Cottage, London on Sunday 2 March 1980, where he was hot to talk drums:

Have you been impressed by any drummers recently?

"Not particularly. It's not that there aren't any good players, it's just when I'm not working, I rarely listen to anybody or go out to clubs. I have my family and I stay home. I find myself involved in a lot of physical exercise and when I go out it's to racket ball and tennis clubs."

You keep up a ferocious rate on stage. How do you do it?

"Well, trying to stay physically and mentally fit. If you have an idea of the directions you want to take your music psychologically, the intensity alone will overwhelm the physical element that has to be put into it. I've been doing a lot of weights over the past few months; I had the time off so I have been able to devote a lot of time to it. I use a club regularly and I can go there each day for a few hours. It does me a lot of good."

How about pacing? When you're playing for one and a half to two hours, pacing is imperative.

"That is a very important element. You have to come to grips with what you can do. Some things you physically cannot do. Make what little you have go past the concert so you have some left over. If you go out and enjoy what you play and contribute to the band rather than showing the audience what you as a drummer can do, you are on the right track. You should not try to overstretch yourself. If you go out with that concept you are already psychologically ahead. the body is only an instrument of the mind so you have to set yourself up right."

You're using three bass drums, and you've obviously got a special pedal arrangement for them.

"Right, there are five bass drum pedals. Two sets of the pedals are set up in tandem by rods, so on the left drum there is a pedal and beater which is attached to a pedal with no beater on the centre drum. There is an independent pedal and beater on this drum and also a pedal with no beater which is attached to a pedal and beater on the right bass drum. So you can see you can play all three drums from the centre. Any combination you want..."

Is there anyone else using this set up?

"Yeah, Louie Bellson, he was the gentleman who made me aware of it. He brought me over to his house one day and said, 'look at this'. I heard he was playing five bass drums before this. I had the same guy who built his set-up build mine. His name is Ollie Oliver."

Do you still use the horn-shaped North drums?

"I'm still using them on occasions – they give a lot of depth, and the tone when projected through the bell shape has a dip to it. It's an interesting concept, like RotoToms and Octobans – specialised percussion. I use them for different combinations of sounds. and I'll throw in some for the forthcoming tour with [bassist] Jack Bruce."

Staccato drums, the British make similar to North, were at the Musik Messe show for the first time. Did you see them?

"Yeah, sure did, they look very, very interesting but I've not heard them yet, so I cannot say how different they'll be from a standard kit."

Any new developments at Tama drums?

"No developments as such. What we are working on together is trying to simplify what we have and trying to make it a lot more obtainable. We are rectifying problems and just trying to make the kits strong with the best projection. Maybe a few changes in the cosmetics, namely colour, there are always new finishes to try. I like the Sunburst finish a lot and want to see that developed. The main thing is for the drums to sound good and stand up to the pressure the musicians put on them."

Lately quite a few drummers have started using on stage effects such as chorus, repeat echo and phasing. Is this new to you?

"No, I've been using them since 1972. I just found my stuff very difficult to transport about. It's very interesting and logical that a lot of bands that are in the forefront today and are lucky enough to sell a lot of records are projecting these images of things that seem to be new, but I've been doing it now for about seven years."

A lot of drummers complain about stage monitoring. It seems there are still a lot of areas for development.

"Funny you should mention that. When I get home I'm taking delivery of a new modular monitoring system made by Peavey. They have made these special systems for Carmine Appice, Aynsley Dunbar and myself. Mine has 28 channels and is positioned right by the kit so I only have to lean over and mix the sound just how I want. the system sends out a sterile signal to the mixing desk in the hall so the engineer can hear it but he cannot mess with it, likewise to the engineer who is controlling the on-stage monitor mix for the rest of the band.

It's great because I'm in total control over what I hear and can adjust the mix accordingly. It's powered by 1600 watts and there is a woofer beneath me with 2 x 12's and a horn on each side plus parametric equalisation. It's a modular system and can be broken down [to suit venue size] accordingly.

How about drum synthesisers? You've been involved with the Snyper but you don't use it much – what happened?

"I told them to come up with something to combat the Synare and Pollard (Syndrum) and the Snyper is what they came up with. I don't use it because it's not enough. All it does is the 'disco swoop'. It's just a joke. Then they made one for me; they claim they won't make for anyone else. It's got eight channels and does everything except wash your face. I use it on movie sessions and it's very interesting, but it's not an instrument."

Do you think there is a future in drum synthesis?

"I have a sneaking suspicion that it will always be around on some level, but what I see now is not the answer."

I think it's down to a lack of experimentation; a lot of players settle for only one or two sounds when there are so many more to use...

"Absolutely, a total lack of experimentation, but people don't have enough time for it. We have enough trouble keeping a job! Recently a lot of stuff has gone back to rock and roll, simple and straight ahead. You go into a studio and do an album in two days for the least amount of money, there is no time for drum synthesisers, a lot have a reputation for being unreliable, you can't afford to spend hours hung up over electrical problems so they get left in the corner and passed over.

I think this is one of the overall problems with synthesisers right now. They are too complex and they take too much time for people. Look at ARP and Avatar. They made this big complex synth, and no one is buying it."

Have you any plans to get back to acoustic jazz?

“Sure I've been playing acoustically for about the past year. I never really left that way of playing. In fact, I've just finished an album for Fantasy with Ron Carter, Kenny Barron and Hubert Laws which is all acoustic. I've also been working with Gil Evans Big band, a 14-piece acoustic line-up, and we've recorded for Toshiba in Japan but it's not out yet.”

This article originally appeared in the July 2024 issue of Jazzwise magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today