Billy Cobham interview: “I was fired from Mahavishnu”

Stuart Nicholson

Thursday, June 13, 2024

Billy Cobham opens up to Stuart Nicholson in an exclusive interview, covering his early life in military bands, tours with Horace Silver, getting fired from the Mahavishnu Orchestra, and his classic jazz-rock album Spectrum

“I was fired from Mahavishnu,” says drum legend Billy Cobham matter-of-factly. After the band played Detroit on 23 December 1973, the musicians went their separate ways. McLaughlin, chastened by the experience, set about regrouping in early 1974.

“It was time for me to be gone,” continues Cobham. “Even though I was told I was going to be in the band, the next thing I knew my last cheque bounced, and I got a message saying, 'you’re no longer with us'; that’s the way management works, and still does today I guess.”

It was a strange ending for a band whose music had, in the space of three short years, redefined the possibilities of jazz-rock. While guitarist John McLaughlin brought a stunning technique and a deep harmonic understanding to the music – “I was conscious of what I wanted to do, the way I wanted to play, nobody else was doing,” he told weekly newspaper Melody Maker – Billy Cobham was similarly taking jazz drumming to the next level. If Tony Williams had been the drummer of the 1960s, then Cobham raised the bar with performances such as ‘Meeting of the Spirits’ from Mahavishnu’s debut Inner Mounting Flame and 'One Word' from follow-up Birds of Fire, become the undisputed drummer of the 1970s.

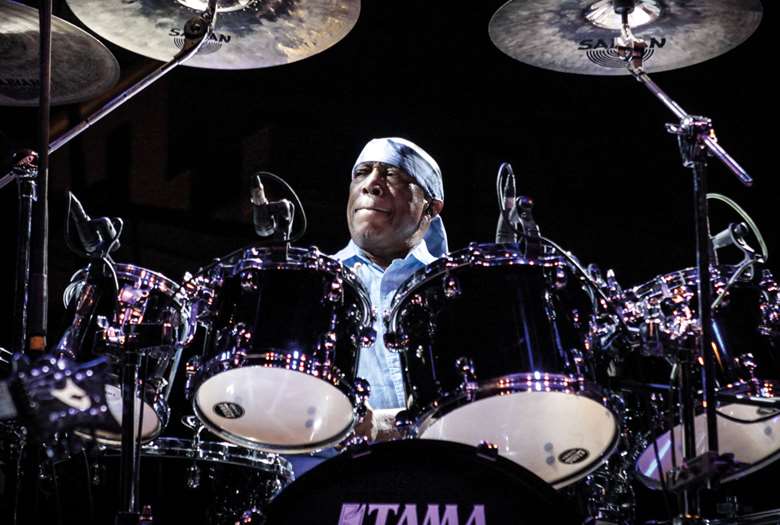

Billy Cobham with the Mahavishnu Orchestra, 1972

Mahavishnu’s intensity, tremendous volume, challenging time signatures and sheer velocity of execution forced Cobham, as he would later admit, to compete physically in terms of stamina and speed, his performances a vital element in the success of the band.

He massively expanded his drum kit with two bass drums; and the array of tuned tom-toms spread out in front were not for decoration. His renowned technical prowess enabled blisteringly fast fills around his tom-toms that still sound awesome today and were imitated by drummers around the world. As the Percussive Arts Society noted, “Billy Cobham is one of the very few who can be called a pivotal drummer in music history. He changed the way we set up our drums and cymbals, he changed the way we play them and he changed the way we play music.”

Ever since his halcyon days in the 1970s and 1980s, Cobham’s performances have been the stuff of legend, combining the techniques of jazz with the visceral power of rock, a compelling duality that audiences love and musicians contemplate in how-does-he-do-it wonder. With the fiftieth anniversary of the release of his hit album Spectrum last year he has once again returned to the touring circuit, and UK audiences will have an opportunity of seeing a living legend as he headlines at the Love Supreme Festival on Saturday 6 July and at his 80th birthday celebration at the EFG London Jazz Festival on Wednesday 20 November at the Queen Elizabeth Hall.

Billy Cobham was born in Panama City on 16 May 1944, but was raised in Brooklyn from the age of three. In those formative years he had two main interests: music and baseball.

“I worked in marching bands as a young person. It was one of the things that kept me off the street. I played baseball in contests everywhere, that’s the thing with being young, you really want to be the best at what you do,” he reflects. Precociously talented, he passed the entrance examination for New York's High School Of Music And Art at the age of 14, an institution that attracted talented students across all New York boroughs, “I walked in with my rudimental procedures off pat because I worked extensively in marching bands. When I attended, my colleagues were Jimmy Owens, Eddie Gomez, Larry Willis – a great jazz pianist but he was a voice major then – Janis Ian, Laura Nyro, Fred Lipsius from Blood Sweat & Tears, Lew Soloff, Bobby Colomby, there was a whole bunch of them, Al Foster, the list goes on, all working their way to graduation. Warren Smith was a teacher there, a great percussionist with Gil Evans. It was perfect for me, not only was it a music school but it was also an art school, so the late Jeremy Steig, known for being proficient playing the flute, was actually a painter. He was studying painting, but he was a good flute player, made some great records. In a situation like in High School, the requirement was that you play together with your colleagues, and to be really good at contributing as a participant; so therefore my foundation was very strong.

“In that kind of environment you learn a lot of things and actually your teachers help you refine them because they are your colleagues. Being young, the competitive element is very high, you don’t want to be following everybody else, you want to be right in the middle of it all rubbing elbows with the best. There was a jazz orchestra called the Marshall Brown Newport Youth Band, and that band was mostly made up of all the kids from my school, and they played the Newport Jazz Festival every year and you’re sitting in an environment where – from my own class was Eddie, Eddie Gomez the bassist, and behind him, sitting right behind him, was Richard Ten Ryk, later known as Richard Tee who played keyboards for Paul Simon, and he also a lot with a band called Stuff – that was who he was. It was just that kind of environment, and the beauty of it all was you didn’t have to pay anything to go to school there, it was one of the special schools the Mayor of New York had way back in the 1940s, a guy named Fiorello LaGuardia, and he created special schools in the humanities, in the arts, for kids into chemistry and the sciences.”

Billy Cobham in the studio, early 1980s

Cobham graduated in 1962: “I was 18 years old, I was just looking for jobs, that’s 1962, so ’63, I'm still looking, just playing around with local bands and stuff like this, and taking on jobs just to help my family out as best I could until a crazy thing happened, and that was the assassination of President Kennedy. That took a toll on me, and at that time was the Vietnam war, so I knew if I didn’t do something to take care of myself I would end up carrying a rifle.

"So I decided to take the examination for the United States Army Band in Washington, and I was fortunate enough to pass and join the army band. And there a lot of schooling began, because I was in the midst of a great group of musicians that also had the same idea – Cecil Bridgewater played trumpet, Grover Washington played not just saxophone but he played bass as well, and a lot arrangers and writers, making up what we needed to do to take care of the USO. It was an organisation to entertain the troops, and I was lucky enough to teach a little music in the Naval School which got me through my time.

“I left the army in January 1968, and I was on the road with Horace Silver at the end of that month until December of the same year, where the last date I played was actually at Ronnie Scott’s at the end of that month after a very long tour – at least for me! I think we did 45 shows with Horace Silver and a junket of bands – Horace, Max Roach’s Quartet, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, a gospel group called The Stars of Faith, and the Elvin Jones Trio with Jimmy Garrison and Joe Farrell. We were all on the bus together. From England we started and had to get a ferry or fly to and from the continent. That’s what I remember about that. A lot of time to pull things together, and all the people involved in those groups, either you gotta to be deaf or totally dumb if you don’t get something out of that!”

Billy Cobham (photo: Tim Dickeson)

On his return to the States, Cobham began taking on dates as a studio musician, as life on the road held few charms for him. Initially working for Atlantic Records, he also did a lot of work CTI Records – he was on 67 albums between 1969–73, with 20 in 1973 alone.

“In New York there was an industry known as studio musicians, and that’s what I thought I wanted to do. I thought if I could excel at that I could be home each day, and that was all okay. What was beautiful about doing stuff for Creed Taylor was that we were working with musicians at a higher level of proficiency, so the chances are you’re going to like the first or second solos that these guys played, no question about it, and it didn’t take a whole lot of time if you have a front line of – hypothetically – Joe Henderson, J.J Johnson and Freddie Hubbard. The thank-yous you get are not in words. When someone calls you on the phone and asks you, ‘Are you free tomorrow for a session that starts at 10am, probably a double session, that’s your thank-you for the things which you did before. They don’t say, 'that sounds good', no, they ask you to come tomorrow. That’s it.

“After while I grew stale, and things were changing anyway because of rock n’ roll, so I ended up on the road with a series of things I felt I could be a better contributor at.”

After he played on one of the Bitches Brew tracks (as well as a number of outtakes), Miles Davis tried to persuade Cobham to join his band. “I really wanted to go out on the road with Miles but on the other side I made the decision, 'what is best for me'; I wasn’t that kind of roamer, I couldn’t just go out and wait until he decided when we were playing, where we were playing, how much we’re getting – something about it just didn’t sit right with me, so I just didn’t do it, that’s all.”

In the event he went briefly with the band called Birdsong, before joining Dreams, with Michael Brecker on tenor sax, John Abercrombie on guitar.

Vibist Mike Mainieri, a close friend of Brecker, saw Dreams several times, stating: “You’ve got to realise they had Billy Cobham, who was a sensation; he could create these kind of pyrotechnic things people had never heard before and when Michael soloed it was so far ahead!”

The band were signed by Clive Davis of Columbia, made two albums and broke up.

“We did have a good time, that band was a great band, and the same thing goes for the Mahavishnu Orchestra," reflects Cobham. “John McLaughlin came to me with some ideas, ‘I have something, do you want to check this out?’ I had time, I was subbing for people like Grady Tate and things like that back then, ‘Are you free today,’ ‘Yeah, what’s up?’ We all lived down in Greenwich Village or down on the West Side, everyone tended to live in this same basic neighbourhood, and there was always something going on – ‘Let’s do this,’ ‘Let’s try that.’ And that’s how Weather Report came together, that’s how Mahavishnu came together, that’s how Eleventh House came together – just co-operations just for the hell of it, and for the love it. I was honoured to be in the middle of all that stuff at that time.”

Without a job after his three years with Mahavishnu, Cobham decided to return to studio work: “If I was going to go back into this field, they’re not going to know me, time goes past very quickly in the studios, people forget quickly, so I wanted to do a recording of what I did as a sampler, and that’s what Spectrum was supposed to be, as far as I was concerned. I handed it out to one or two people, but primarily it was for Mom and Dad – ‘Hey, I made a record!’ – and that was it. Six months later, I’m in the studios anyway and people kept telling me my record was good and I thought they were referring to records I had recorded in support of other artists on, until the head of artist development at Atlantic phoned and said, ‘Where have you been? We’ve been trying to find you.’”

Without Cobham knowing, Spectrum (1973), reached No. 1 on the Billboard magazine Jazz Albums chart and No. 26 on the Top 200 Albums chart. With encouragement from the record company he formed a band to tour the album: “Naturally I called John [Abercrombie], the Brecker Brothers, people that I knew, and said, ‘Come on, let’s go out and do this!’ No problem. It was easy. I was out there by myself, and I had to do what I could, we made it work.”

Last year was the 50th anniversary of Spectrum, and naturally enough Cobham formed the Spectrum 50 band to celebrate the occasion. But when he takes the stage for the Billy Cobham at 80 celebration at the EFG London Jazz Festival in November it will be an ambition fulfilled as he will be performing his compositions with a full orchestra.

“Billy has always said he would love to perform his compositions with a symphony orchestra during the time I have known him,” says trumpeter, arranger and composer Guy Barker. “Then he phoned out of the blue to say, ‘We can do it!' So I am arranging the music for his Spectrum 50 Quartet plus the BBC Concert Orchestra plus my big band, so it will be quite a lot of people on the stage! We will be dong new orchestrations of repertoire including ‘Red Baron,’ ‘Spectrum,’ ‘Crosswinds,’ ‘Stratus,' and ‘A Funky Thide of Sings’ plus new material he has written, such as ‘Mirage’ for example. The man is a living legend, he really is, and this show will be something special.”

Billy Cobham’s Spectrum 50 Band plays Love Supreme Jazz Festival on 6 July; and the EFG London Jazz Festival on 20 November at the Queen Elizabeth Hall

This article originally appeared in the July 2024 issue of Jazzwise magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today