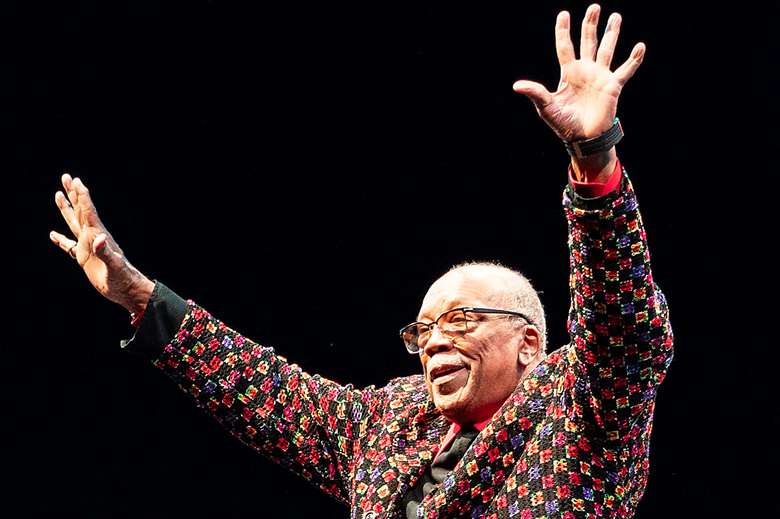

Quincy Jones: 14/03/33 – 03/11/24

Alyn Shipton

Tuesday, November 5, 2024

Alyn Shipton pays tribute to the globally renowned writer, arranger, producer and trumpeter whose long career was steeped in jazz – including early work with the likes of Dizzy Gillespie and Lionel Hampton – long before his huge successes with George Benson and Michael Jackson

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Jazzwise.co.uk. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, live reviews and artist pages

- Free email newsletter